HAV is a non-enveloped RNA virus that is resistant to viral reduction processes in plasma product manufacturing. Transmission of HAV is primarily by the fecal-oral route (i.e., interpersonal contact, hand-to-mouth, contaminated food or water). Common exposure risks include travel to developing countries, close household contact, and food-borne outbreaks associated with HAV-contaminated raw or uncooked products. Additionally, HAV may be transmitted by the transfusion of fresh blood components, plasma protein products, and pathogen-reduced platelets and plasma. HAV is not endemic in Canada, with an annual rate of 1/100 000 often related to travel to endemic areas.1

FAQ: Hepatitis A Virus (HAV) at Canadian Blood Services

Authors: Nicole Relke, MD, FRCPC; Mark Bigham, MD, MHSc, FRCPC; Aditi Khandelwal, MSc, MD, FRCPC, DRCPSC.

Publication date: October 6, 2025

Primary target audience: Transfusion medicine staff in hospitals

Background

Hepatitis A virus (HAV) can be transmitted through blood and blood products including pathogen-reduced platelets and plasma, and purified plasma protein products. Plasma fractionators report plasma nucleic acid test (NAT) results for HAV to Canadian Blood Services within a time frame that may incur the recall of in-date products. These test results may result in follow up management by the hospital who received the product(s) and further management if it was transfused.

Frequently asked questions

1. What is hepatitis A virus (HAV)?

2. What are symptoms of HAV infection?

HAV infection is usually asymptomatic in young children, however most older children and adults develop symptomatic illness ranging from non-specific flu-like symptoms (i.e., fatigue, fever, nausea, or vomiting) to acute hepatitis (i.e., abdominal pain, jaundice). Extra-hepatic symptoms due to immune complex disease may occur including rash, arthralgia, hemolytic anemia, pancreatitis, vasculitis, and renal disease.

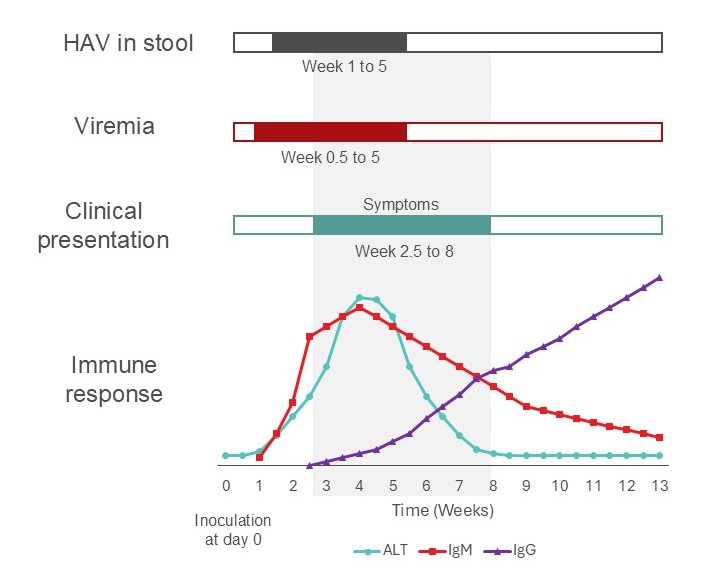

Most people are sick for 1–2 weeks and then recover. Although there is no chronic form of HAV infection, a small number of patients may develop prolonged infection for up to a year. Less than 1% of immunocompetent individuals who contract HAV develop severe liver failure (fulminant hepatitis). Prior infection and immunization lead to life-long immunity. See Figure 1 for HAV course of illness.

Figure 1. Time course for a typical case of hepatitis A illness in an immune competent adult. Acutely infected individuals may donate potentially infectious blood during the incubation period.

3. Are some people at a higher risk of complications from HAV?

Yes, HAV infection can cause more serious complications in patients with pre-existing chronic liver disease (e.g., hepatitis B or hepatitis C) or immunosuppressed people (e.g., immunosuppressive medication, HIV, stem cell transplantation). Once acquired, HAV symptoms can last up to 3 months in these higher risk patients.

4. Can HAV infection be prevented?

Pre- or post-exposure hepatitis A vaccination and/or immunoglobulin can prevent or reduce the risk of hepatitis A virus infection. Vaccination usually provides life-long protection.

5. What is the risk of HAV transmission through blood?

The risk of HAV transmission through blood transfusion is rare; approximately 40 cases have been reported since 1970.2 Viremia for HAV occurs 7–14 days prior to symptom onset, so a donor may feel well during their donation and for several weeks after before symptoms begin (see Figure 1).

7. Why does Canadian Blood Services collect information on HAV from the fractionator and what do they do with positive results?

When informed by the fractionator of positive HAV NAT results, Canadian Blood Services currently recalls all associated components collected up to 4 months prior to positive test results and 6 months following an implicated donation. Epidemiology of HAV in Canada and within the donor population is also tracked by Canadian Blood Services.3

8. I received a recall notice from Canadian Blood Services indicating that a donor is positive for HAV. What does this mean for a patient who received a potentially infectious blood transfusion?

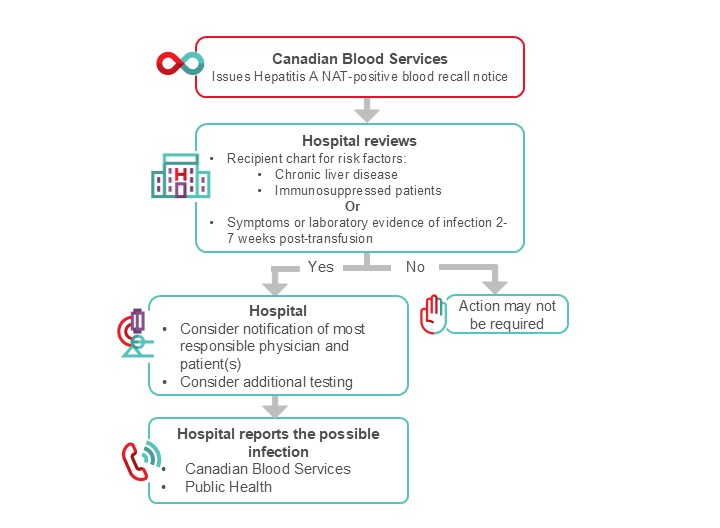

Transfusion recipients who are HAV-susceptible (i.e. not previously immunized or infected, or immunocompromised) are potentially at risk of transfusion-transmitted HAV infection. HAV symptoms may develop 2–7 weeks after transfusion. If infected, the recipient could potentially be infectious to others; HAV infection may be transmitted through close contact over a four-week period, starting about 2 weeks prior to onset of symptoms.

If a patient has received a co-component (i.e., platelets or red blood cells) from a HAV positive donor, a review of the patient’s chart and discussion with the patient’s attending physician is recommended. Notifying the recipient of the transfusion is also recommended. Pathogen-reduction technology is less effective against HAV and pathogen-reduced platelet or plasma products may still be infectious.

HAV-susceptible transfusion recipients and their household and close contacts should be assessed for post-exposure prophylaxis as soon as possible after hospital notification (i.e., hepatitis A vaccine and/or serum immune globulin, depending on age and underlying medical conditions).

Figure 2. Suggested algorithm for hospital transfusion medicine staff for the management of HAV NAT positive recall.

9. I assessed that a possible transfusion-transmitted HAV infection occurred. What reporting is required?

If you assess that a possible transfusion-transmitted HAV infection occurred, please report this to Canadian Blood Services. HAV is also a reportable infection to Public Health in all provinces and territories. Public Health can provide guidance regarding post-exposure prophylaxis.

Additional resources

For more information on Hepatitis A visit:

Hepatitis A | Public Health Ontario

- Resources on this page include a Fact sheet and infographic, surveillance report, data analysis, and more

AABB Hepatitis A virus Information sheet at: https://www.aabb.org/regulatory-and-advocacy/regulatory-affairs/infectious-diseases/emerging-infectious-disease-agents

Suggested citation

Relke, N., Bigham, M. & Khandelwal, A. (2025, October 6) FAQ: Hepatitis A Virus (HAV) at Canadian Blood Services. Canadian Blood Services. Retrieved Month day, year, from: https://profedu.blood.ca/en/faq-hepatitis-virus-hav-canadian-blood-services

References

- Ontario, P. H. (2024). Hepatitis A. https://www.publichealthontario.ca/en/diseases-and-conditions/infectious-diseases/enteric-foodborne-diseases/hepatitis-a

- Viral agents (2nd section). (2024). Transfusion, 64(S1), S66-S69. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/trf.17630

- Drews, S. J., Charlton, C., O'Brien, S. F., Burugu, S., & Denomme, G. A. (2024). Decreasing parvovirus B19 and hepatitis A nucleic acid test positivity rates in Canadian plasma donors following the initiation of COVID-19 restriction in March 2020. Vox Sang, 119(6), 624-629. https://doi.org/10.1111/vox.13616