Chapter 19

Pathogen-reduced platelets

Last updated: May 24, 2023

Primary target audiences: transfusion medicine physicians, non-transfusion medicine physicians, nurses, medical laboratory technologists in a hospital laboratory.

The purpose of this chapter is to provide information about pathogen-reduced platelets, a blood component manufactured by Canadian Blood Services starting in 2022. Other terms describing pathogen-reduced platelets include INTERCEPT platelets, pathogen reduction technology (PRT) platelets, and psoralen-treated platelets. Pooled platelet psoralen-treated (PPPT) and apheresis platelet psoralen-treated (APPT) refer to specific types of pathogen-reduced platelets. Pathogen inactivation technology (PIT) refers to the technology used to produce pathogen-reduced platelets.

This chapter provides information about pathogen-reduced platelet manufacturing, component characteristics, and safety. It also compares pathogen-reduced platelets to untreated platelets in terms of component characteristics, clinical benefits, and drawbacks.

Introduction

Blood components can become contaminated with bacteria from the skin of donors during blood donation or, less often, from the donor’s blood stream.1,2 Platelet components face a greater risk of bacterial contamination because they are stored at room temperature. Canadian Blood Services surveillance data from 2006–2016 showed that bacterial sepsis occurred in 1 in every 125,000 transfused platelet concentrates.3 In 2020, Canadian Blood Services identified true and suspected positive bacterial contamination in 175 (of 105,720) platelet components.1

To reduce the risk of bacterial contamination, a number of mitigation strategies have been implemented, including the introduction of diversion pouches during whole blood collection4 (see Chapter 6 for more on the blood collection process) and large volume delayed bacteria culture sampling.5 At Canadian Blood Services, untreated platelets are routinely screened for bacterial contamination using microbial culture methods of the BACT/ALERT 3D system. Although implementation of an enhanced large volume bacterial detection screening algorithm resulted in a threefold reduction in septic transfusion reactions5, risk of bacterial contamination remains higher than that of other transfusion-transmitted infections.1 For more information on platelet bacterial testing see our FAQ: Canadian Blood Services platelet bacterial screening.

To improve blood safety, many countries have implemented pathogen inactivation technologies to reduce the risk of bacterial transmission.1,6 In December 2021, Health Canada approved the use of Cerus INTERCEPT Pathogen Inactivation Technology (PIT) for manufacturing pooled platelets psoralen-treated (PPPT) at Canadian Blood Services. PPPT was introduced by Canadian Blood Services at select hospitals in January 2022. Following Health Canada approval in May 2023, apheresis platelet psoralen-treated (APPT) and untreated apheresis platelet in PAS-E are being implemented in Ottawa on June 12, 2023 with a national implementation to follow (see Customer Letter CL 2023-03).

Pathogen inactivation technology

Pathogen inactivation technology reduces the risk of transfusion-transmitted pathogens and provides an additional layer of safety against:7

- Viruses (enveloped and non-enveloped)

- Including HIV-1, cell-associated, HTLV-I/II, West Nile virus, chikungunya virus, cytomegalovirus (CMV), influenza A virus

- Bacteria (gram-positive, gram-negative and spirochetes)

- Including Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Treponema pallidum (syphilis),8 Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme disease)

- Protozoan parasites

- Including Plasmodium falciparum, Babesia microti, Trypanosoma cruzi

- White blood cells (leukocytes)

- Human T cells

Mechanism of action

Amotosalen S-59 (amotosalen) is the active photoreactive compound of the Cerus INTERCEPT pathogen inactivation system. Amotosalen, a synthetic psoralen, intercalates within nucleic acids that compose the DNA and RNA of organisms and viruses. After addition to the platelet component through a specialized process, amotosalen becomes activated when exposed to ultraviolet A (UVA, 320–400 nm) illumination. This causes permanent crosslinking between the nucleic acid strands of viruses, bacteria, protozoa, and leukocytes that may contaminate the platelet unit. Crosslinking damages DNA and RNA leading to pathogen and leukocyte inactivation. Amotosalen does not exhibit specificity towards genetic material of any particular organism or nucleic acid sequence. Thus, any cellular material with DNA or RNA may be modified by amotosalen, including donor-derived platelets and white blood cells. The inactivation of genetic material in donor platelets does not adversely affect platelet function.

After addition of amotosalen and illumination with UVA light, platelets are transferred to a bag containing a compound adsorption device that removes residual amotosalen and its free photoproducts. The bag is agitated for up to 16 hours. The material in the compound adsorption device decreases the amotosalen from 150 µmol/L to 0.5 µmol/L post-adsorption.9

Efficacy

Amotosalen has been studied with enveloped and non-enveloped viruses, gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria, and parasites. Infectious disease burden is measured as the log reduction from the original spiked inoculum. Efficacy varies by organism, with most pathogen reduction occurring at greater than 3 log.

Table 1: Efficacy of INTERCEPT inactivation technology on viruses, bacteria and parasites in platelet additive solution (PAS). Data sourced from Cerus‡ and published studies†*.

| Enveloped viruses | Log reduction | Non-enveloped viruses |

Log reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-1, cell free HIV-1, cell-associated HBV HCV HTLV-I HTLV-II Cytomegalovirus Bovine viral diarrhea virus† West Nile virus Chikungunya Influenza A virus SARS-CoV-2* Dengue virus† Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus† |

≥5.6 ≥5.4 ≥4.8 ≥4.1 4.7 ≥5.1 ≥4.9 >6.0 ≥6.3 ≥5.7 ≥5.9 >3.31 >5.2 2.9 |

HAV† Parvo B19† Blue tongue virus Human adenovirus Calicivirus |

0 >6.2 5.2 ≥4.9 2.1 |

| Gram-positive bacteria | Log reduction | Gram-negative bacteria | Log reduction |

| Bacillus cereus (incl. spores) Bacillus cereus (vegetative) Bifidobacterium adolescentis Clostridium perfringens (vegetative) Corynebacterium minutissimum Listeria monocytogenes Proprionobacterium acnes Staphylococcus aureus Staphylococus epidermidis Streptococcus pyogenes Lactobacillus species† |

3.7 ≥5.5 ≥6.0 ≥6.5 ≥5.3 ≥6.3 ≥6.5 ≥6.6 ≥6.4 ≥6.8 >6.9 |

Escherichia coli Enterobacter cloacae Klebsiella pneumonia Pseudomonas aeruginosa Salmonella cholerasuis Serratia marsescens Yersinia enterocolitica |

>6.3 >6.6 >6.2 ≥6.7 6.2 ≥6.7 ≥5.9 |

| Parasites | Log reduction | Spirochetes | Log reduction |

| Babesia microti Leishmania major+ Leishmania mexicana Plasmodium falciparum Trypanozoma cruzi |

≥4.9 >4.3 ≥5.0 ≥6.6 ≥7.8 |

Borrelia burgdorferi Treponema pallidum |

≥6.8 ≥6.4 |

|

† Schlenke P. Pathogen inactivation technologies for cellular blood components: an update. Transfus Med Hemother. 2014;41(4):309-325. * Hindawi SI, El-Kafrawy SA, Hassan AM, et al. Efficient inactivation of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) in human apheresis platelet concentrates with amotosalen and ultraviolet A light. Transfus Clin Biol. 2022;29(1):31-36. doi:10.1016/j.tracli.2021.08.005 ‡ Cerus website. https://intercept-usa.com/what-is-intercept/intercept-platelets/broad-spectrum-pathogen-reduction/ |

|||

In vitro studies have shown that amotosalen with UVA light effectively inactivates leukocytes compared to irradiation.10, 11 A cohort study of hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients who received pathogen-reduced platelets that were both not irradiated nor leukoreduced reported excellent safety outcomes.12 There have been no cases of transfusion associated graft versus host disease (Ta-GVHD) reported following transfusion with pathogen-reduced platelets from clinical studies or hemovigilance databases. Pathogen-reduced platelets are considered equivalent to an irradiated component and do not require irradiation under any circumstances.

Safety profile of amotosalen

The toxicity of psoralen-based treatments has been extensively studied. The amount of residual amotosalen after platelet preparation is much lower than the toxic threshold. Mouse models exposing neonatal rats to high concentrations of amotosalen (up to 48 fold of the expected dose in adult patients) showed no toxicity.13Acute and chronic amotosalen toxicity has also been evaluated in studies of escalating doses of INTERCEPT platelets and measured amotosalen levels.14 Doses that triggered acute toxicity in animal studies are 150,000 times (rat studies) and 30,000 times (dog studies) higher than what would be delivered in a platelet dose to humans.15 Additionally, amotosalen is water soluble and rapidly excreted. Thus, trace amounts of the compound in blood components will not bioaccumulate.2

INTERCEPT has been approved for use in the European Union since 2002 and gained FDA approval in the United States in 2014. Clinical trials and large multinational hemovigilance databases have confirmed the excellent safety profile seen in preclinical studies.16,17,18

Manufacturing and component descriptions of pathogen-reduced platelets

The production of pathogen-reduced platelets—both pooled platelet psoralen-treated (PPPT) and apheresis platelet psoralen-treated (APPT) platelets—will be outlined separately below. The manufacturing of untreated apheresis platelets in PAS-E (the formulation of platelet additive solution used at Canadian Blood Services) will also be described. Table 2 provides a component characteristic summary of the two existing platelet components (untreated apheresis platelet in plasma, untreated buffy coat platelet in plasma) and the three new platelet components, all suspended in platelet additive solution (PPPT, APPT, untreated apheresis platelet in PAS-E).

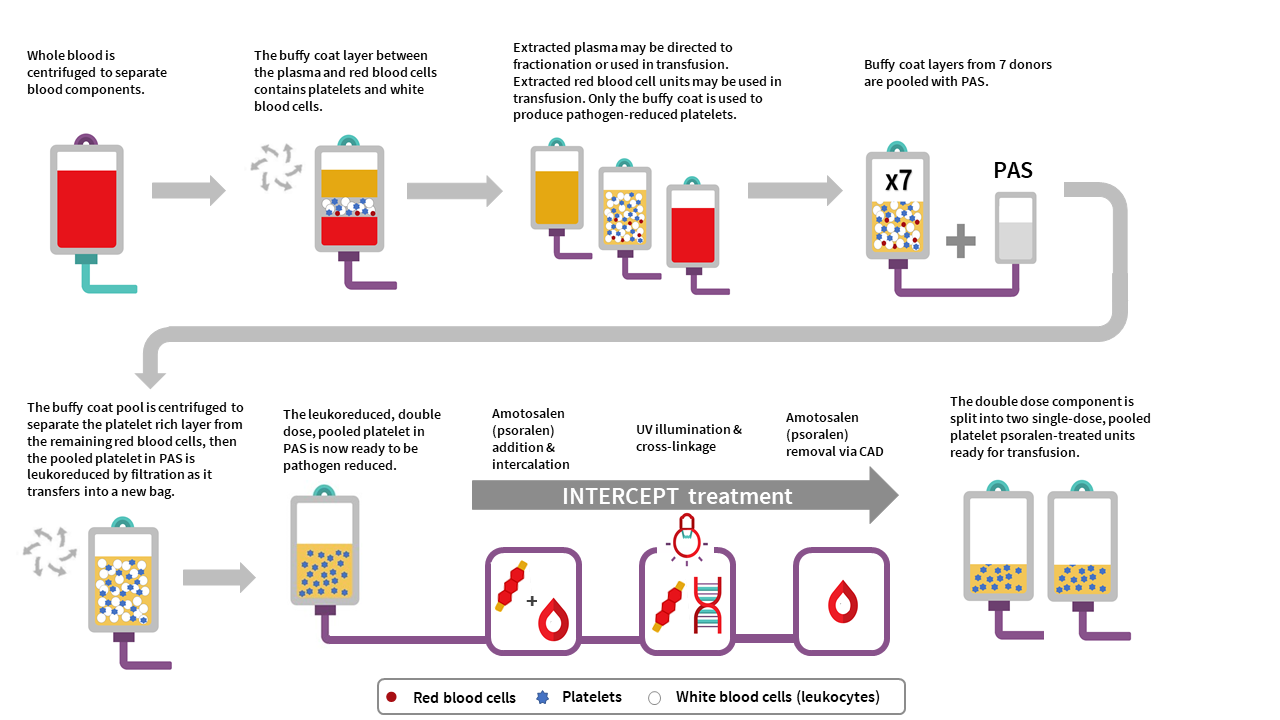

Pooled platelet psoralen-treated (PPPT) manufacturing

The manufacturing of PPPT begins with the collection of whole blood into buffy coat collection sets from donors in a Canadian Blood Services donor centre. Whole blood units are centrifuged to separate the plasma, buffy coat (containing leukocytes and platelets) and red blood cell fractions. The red cell and plasma layers are extracted out of the collection bag leaving behind the buffy coat layer with a small amount of plasma and red blood cells (also referred to as the B1 method as described for whole blood buffy coat collections). Seven buffy coats—one from each donor unit— are then pooled together and platelet additive solution (PAS-E) is added. The buffy coat pool is then centrifuged, and the platelet-rich supernatant (comprised of residual plasma and PAS-E) is extracted from the red blood cells retained in the buffy coat through a platelet-sparing leukoreduction filter, to produce a double dose pooled platelet.

Amotosalen is then added to the double dose pooled platelet unit, and the double dose pooled platelet unit undergoes treatment with UVA illumination to facilitate crosslinking of amotosalen to residual nucleic acid material within the unit. A single treatment with UVA can adequately intercalate DNA and RNA from donor cells and pathogens within a range of concentrations. Residual amotosalen and its photoproducts are then removed by incubating the double dose pooled platelet with a compound adsorption device. The double-dose PPPT unit is then split into two single-dose PPPT units.

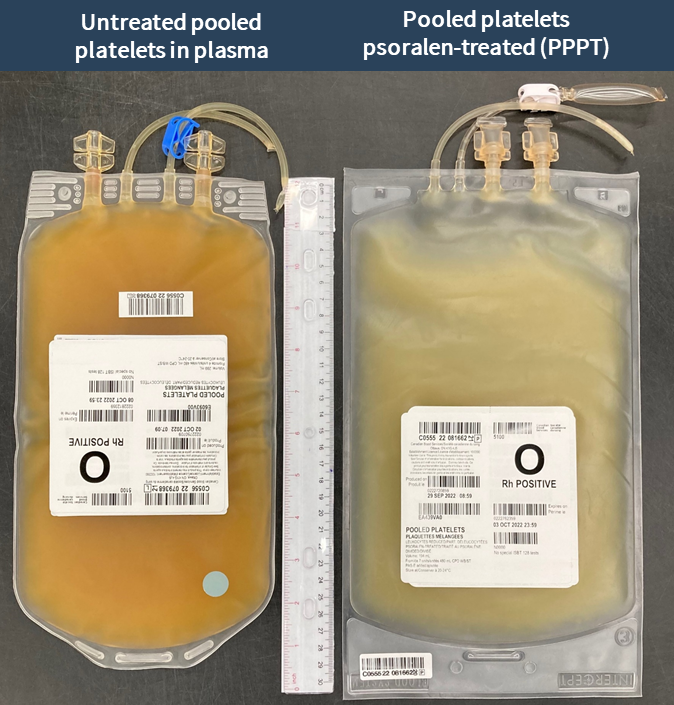

PPPT component characteristics

Pooled, pathogen-reduced platelets are manufactured from seven donor (male or female) buffy coats, which are pooled together to create an individual double-dose unit that is then divided into two separate units. In contrast, current untreated pooled platelet in plasma units at Canadian Blood Services are created with buffy coats from up to three individual female donors and at least one male donor, resuspending the platelets in the male plasma. While PPPT are derived from more donors (seven donors) than untreated pooled platelets (four donors), the total volume of plasma in a unit of PPPT is less than the total volume of plasma in a unit of untreated pooled platelets. This is because the PPPT product is pooled in PAS-E rather than male plasma (PAS-E:plasma ratio is approximately 60%:40%). See Table 2 for summary of product characteristics. Note the lower platelet yield, and differences in volume and mean platelet count, of PPPT compared to the untreated pooled platelet component.

The residual white blood cell count post-filtration in a double-dose unit of PPPT is 0.04±0.06 x 106 cells/unit, which is comparable with the residual white blood cell count post-filtration in untreated pooled platelets in plasma (0.04±0.09 x 106 cells/unit). Additionally, the few residual white blood cells in PPPT are inactivated by amotosalen and UVA light.

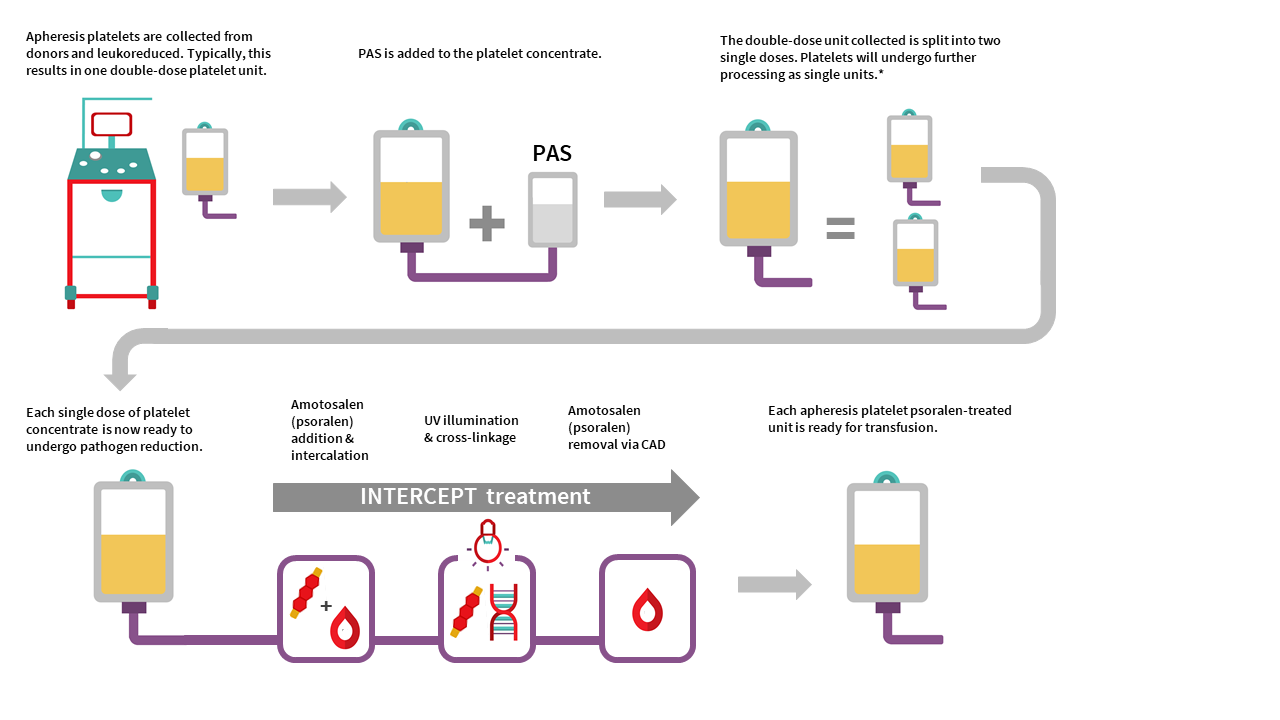

Apheresis platelet psoralen-treated (APPT) and untreated apheresis platelet in PAS-E manufacturing

Manufacturing of APPT begins with single donor apheresis platelet donation performed in a Canadian Blood Services donor centre. In contrast to whole blood collection, plateletpheresis is performed using the Terumo Trima apheresis collection system, which extracts platelets and donor plasma from whole blood. Each collection yields one single dose platelet unit or one double dose platelet unit. Platelets are leukoreduced by the Trima system during collection in a hyperconcentrated form with a small amount of plasma. Platelet additive solution is then added to achieve the desired PAS-E:plasma ratio (approximately 60%:40%) for each platelet unit. Each resulting single-dose apheresis platelet unit is then pathogen inactivated with addition of amotosalen and exposure to UVA illumination described in the process above for PPPT. Residual amotosalen is removed by incubating the unit with a compound adsorption device before units are ready for use.

The manufacturing of an untreated apheresis platelet in PAS-E is similar to APPT manufacturing, except no pathogen inactivation would occur (no amotosalen treatment and no UVA light exposure). Routine sterility testing as performed on our current apheresis platelets in plasma using the BacT/ALERT system would ensue after manufacturing (see the FAQ on Canadian Blood Services platelet bacterial screening).

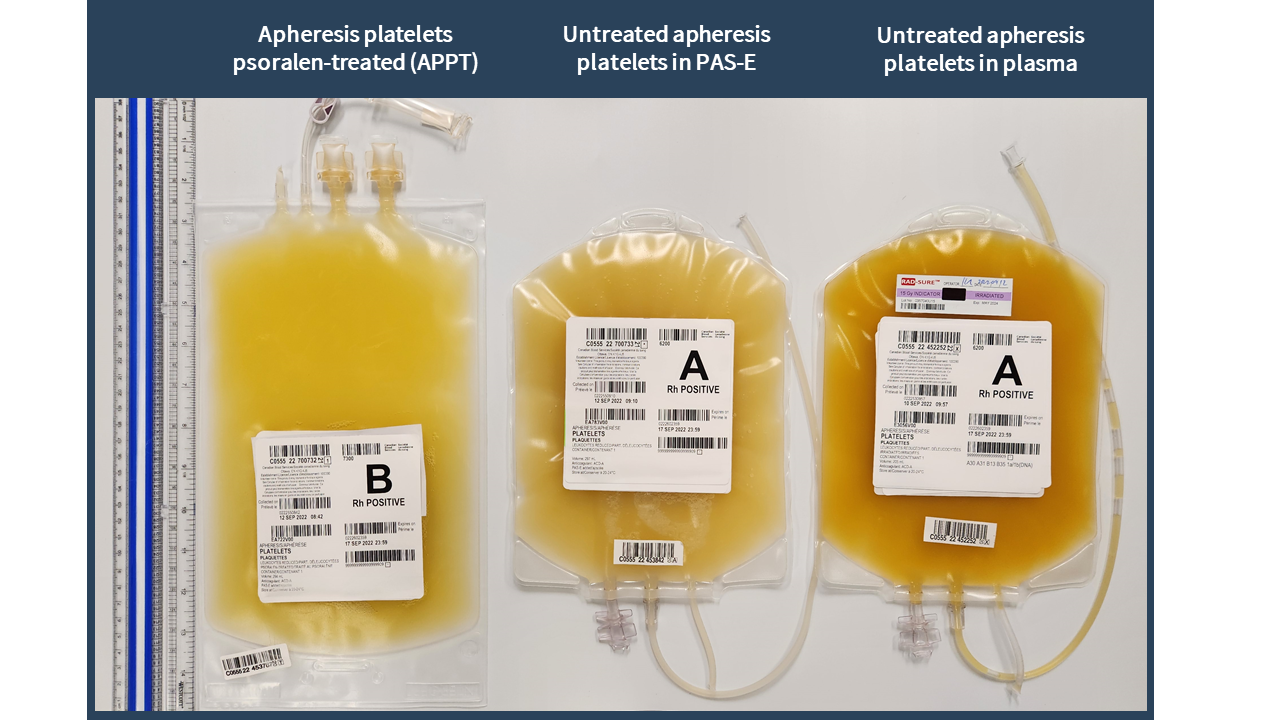

APPT and untreated apheresis platelet in PAS-E component characteristics

APPT and untreated apheresis platelet in PAS-E are manufactured from individual male or female donors. Typically, collection results in one double dose platelet unit but may result in a single dose platelet unit. There is no pooling with additional donors. See Table 2 for summary of component characteristics. Note the differences in volume, mean platelet count, and platelet yield of APPT and untreated apheresis platelet in PAS-E compared to the untreated apheresis platelet component in plasma. Note all values are product development data only and may change following product validation and implementation.

The residual white blood cell count after on-instrument leukoreduction for an apheresis platelet component in PAS-E is approximately 0.04 x 106 cells/unit, compared with the residual white blood cell count post-filtration in untreated apheresis platelets in plasma of 0.09 ± 0.22 x 106 cells/unit. Additionally, the few residual white blood cells in the APPT component are inactivated by amotosalen.

Packaging and labeling

PPPT and APPT are stored in gas-permeable ethylene vinyl acetate bags. Untreated apheresis platelets in PAS-E are stored in gas-permeable poly vinyl chloride n-butyryl-tri-n-hexyl citrate (PVC-BTHC) bags. These bags do not contain any di-ethyl hexyl phthalate (DEHP) plasticizer; however, the attached transfusion ports and tubing may be made of plastics that contain DEHP. Platelet units may also come into contact with DEHP plasticizer during collection and component manufacturing.

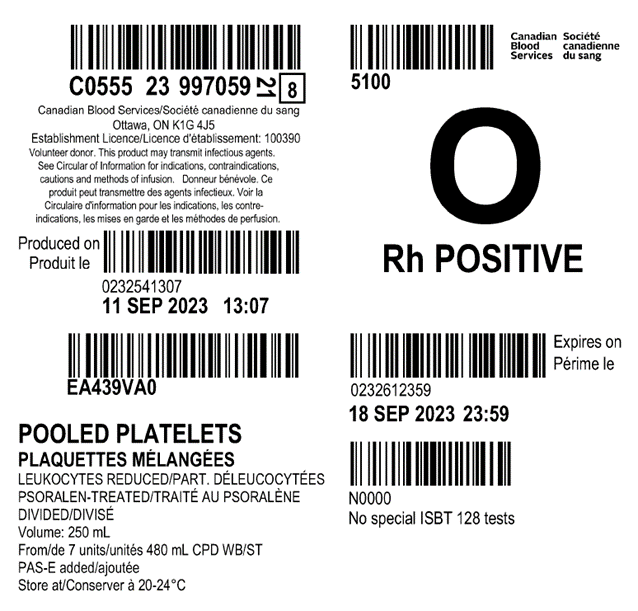

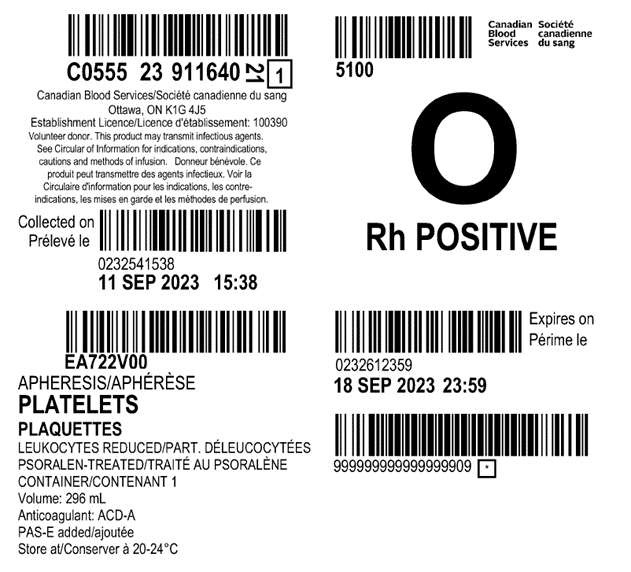

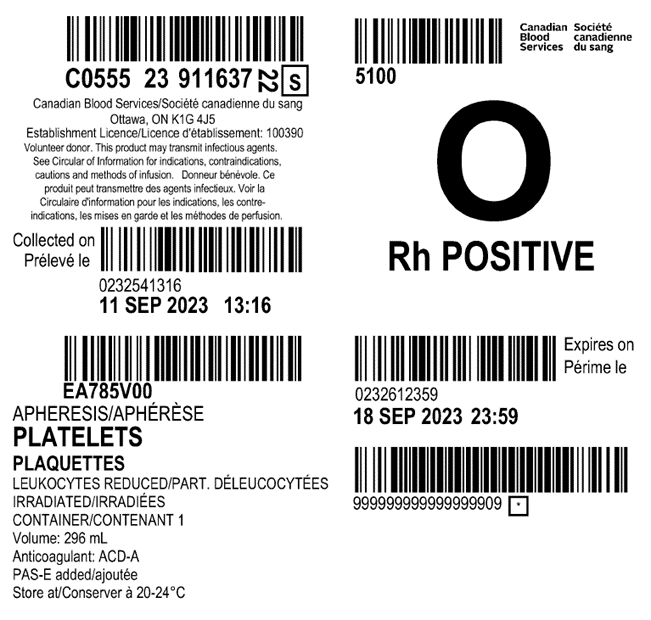

Examples of labels for PPPT, APPT, untreated apheresis platelet in PAS-E components are available below. Please note that you can find ISBT codes and further label examples in Customer Letters 2022-18 and 2022-34. Contact your regional Canadian Blood Services Hospital Liaison Specialist if you require additional label examples.

Table 2: Summary component characteristics of existing and new platelet components.

| Existing platelet components in plasma (prior to 2022) | New platelet components in PAS-E (as of 2022) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component characteristic | Untreated pooled platelet | Untreated apheresis platelet | Untreated apheresis platelet in PAS-E | Pooled platelet psoralen-treated (PPPT) | Apheresis platelet psoralen-treated (APPT) |

| Untreated (not pathogen-reduced) | Pathogen-reduced | ||||

| Mean unit volume (mL) | 317 | 223 | 269 | 184 | 277 |

| Number of donors in component | 4 | 1 | 1 | 7‡ | 1 |

| Mean plasma volume (mL) | 317 (approximately 20 mL from each of 3 donors + 257 mL plasma from one male donor) | 223 | 113 | 75 (approximately 11 mL per donor) | 116 |

| Approximate platelet count (x109 platelets per L) | 1,069 | 1,493 | 1033 | 1,363 | 909 |

| Approximate platelet yield (x109 platelets per unit) | 339 | 333 | 279 | 251 | 252 |

| Resuspension solution | Plasma | Plasma | Approx. 60% platelet additive solution (PAS-E) + 40% Plasma |

Approx. 60% platelet additive solution (PAS-E) + 40% Plasma |

Approx. 60% platelet additive solution (PAS-E) + 40% Plasma |

| Anticoagulant | CPD | ACD-A | ACD-A | CPD | ACD-A |

| Bacterial screening performed by Canadian Blood Services | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Typical time to release component to hospital after blood collection from donor | Day 3 | Day 3 | Day 3 | Day 2 | Day 2 |

| Component shelf life (from day of blood collection) | 7 days | 7 days | 7 days | 7 days* | 7 days |

| Viable lymphocytes present? | Yes, irradiation required for vulnerable patients¥ | Yes, irradiation required for vulnerable patients¥ | Yes, irradiation required for vulnerable patients¥ | Viable lymphocytes not present, irradiation not required for vulnerable patients | Viable lymphocytes not present, irradiation not required for vulnerable patients |

|

Note: Component characteristics for untreated pooled and apheresis platelets in plasma are available in Canadian Blood Services Circular of Information for platelets.19 Component characteristics for PPPT, APPT and untreated apheresis platelet in PAS-E are available in Canadian Blood Services' Circular of Information.3 ‡ PPPT components are manufactured from 7 donor (male or female) buffy coats, which are pooled together and then divided into 2 separate units for transfusion. Note the lower platelet yield of the PPPT component compared to the untreated pooled platelet component. * The shelf life of PPPT was increased from 5 to 7 days on April 24, 2023. ¥ See the National Advisory Committee on Blood and Blood Products' Recommendations for Use of Irradiated Blood Components in Canada. |

|||||

Platelet additive solution (PAS)

PAS is a crystalloid nutrient media designed to replace a portion of plasma within platelet units. PAS-E (the formulation of PAS used at Canadian Blood Services) is added to the PPPT, APPT, and untreated platelets in PAS-E components (see Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Canadian Blood Services will use Macopharma SSP+ (PAS-E) solution to suspend platelets prior treatment with the INTERCEPT system. It contains sodium citrate dihydrate 3.18 g, sodium acetate trihydrate 4.42 g, sodium dihydrogen phosphate dihydrate 1.05 g, disodium phosphate anhydrous 3.05 g, potassium chloride 0.37 g, magnesium chloride hexahydrate 0.30 g, sodium chloride 0.37 g, magnesium chloride hexahydrate 0.30 g, and sodium chloride 4.05 g per 1,000 mL of water. SSP+ is relatively inert compared to plasma. The final ratio of PAS-E:plasma in PPPT, APPT, and untreated apheresis platelets in PAS-E is about 60:40.

PAS clinical data

PAS has several benefits as an alternative to plasma for platelet suspension due to dilution of plasma proteins, cytokines, iso-agglutinins, and other bioactive molecules in the platelet component. PAS platelets have an approximately 50% lower risk of allergic transfusion reactions compared to plasma-stored platelets as reported in clinical studies20-23 and hemovigilance databases.24,25 In some studies, PAS platelets have been associated with a lower risk of febrile non-hemolytic transfusions.22,25 Among HLA antibody positive donors, PAS platelets have fewer HLA antibody specificities compared to plasma suspended platelets26 and, thus, may theoretically reduce the risk of transfusion associated acute lung injury (TRALI).20,27 However, low incidence of TRALI and implementation of other TRALI-mitigation strategies make it difficult to determine if and how PAS impacts TRALI.20

Replacement of plasma with PAS reduces the amount of anti-A, anti-B, and anti-AB isoagglutinins. A 50% reduction in isoagglutinin titers has been reported comparing PAS to plasma-suspended platelets.26,28,29 In one prospective study, 356 PAS platelets were found to have anti-A and anti-B antibody titres lower or equal to 1:32, and most of the units had titres below 1:8; ABO incompatible platelets were transfused without issue in this study.30 There is no widely accepted critical anti-A/B titer that consistently predicts clinically significant hemolysis.31 The risk of hemolytic transfusion reactions is also more complex than the titre levels alone.32 PAS may therefore theoretically improve the safety of incompatible platelet transfusions with potential inventory and wastage impacts.29 Canadian Blood Services cannot make any claims about the final antibody titres at this time. Case reports of hemolytic transfusion reactions following PAS platelets have been reported.33

From a bleeding risk standpoint, platelets suspended in older formulations of PAS led to lower corrected count increments compared to plasma.21,34,35 Newer formulations of PAS (such as PAS-E used by Canadian Blood Services) have shown improved corrected count increments at 1-24 hours compared to older PAS formulations.36 No differences in bleeding complications and transfusion intervals following transfusion with platelets suspended in PAS versus platelets suspended in plasma have been reported in clinical trials.35

Benefits

Pathogen-reduced platelets are associated with multiple benefits as outlined below.

Reduces risk of bacterial transmission

Pathogen inactivation of platelet components significantly reduces the risk of transfusion-transmitted bacterial infections.37,38 Swiss hemovigilance data from 2011-2016 following implementation of pathogen-reduced platelets reported 0 cases of transfusion-transmitted bacterial infection (out of 205,574 issued platelet components)18 In contrast, between 2005-2011 prior to implementation of pathogen-reduction, there were 16 reported cases of transfusion-transmitted bacterial infections (out of 158,502 issued platelet components). A prospective hemovigilance study across 11 European countries of 19,175 pathogen-reduced platelet transfusions also identified no cases of transfusion-transmitted bacterial infection, further supporting the safety and efficacy of PIT.17

Reduces risk of other transfusion-transmitted infections

Since amotosalen nonspecifically intercalates in the DNA and RNA of organisms and viruses, PIT provides an additional layer of safety for platelet components against known and unknown pathogens. It complements the donor selection criteria and pre-transfusion pathogen testing performed on all donations (see Chapter 6 of the Clinical Guide to Transfusion). Infectious disease testing will continue as part of Canadian Blood Services' blood donor screening process; however, bacterial testing with the BACT/ALERT 3D system will not be required for pathogen-reduced platelets. The efficiency of amotosalen inactivation varies by pathogens.

Some pathogens are resistant to amotosalen treatment (e.g., hepatitis A, hepatitis E, poliovirus, and prions).7 Pathogen inactivation efficacy may be affected by large pathogen burden, poor light energy delivery due to interfering substances, and/or potential human error during blood processing.39,38

Favorable safety profile

Safety endpoints from clinical trials and published hemovigilance data demonstrated no statistically significant change with respect to serious adverse events, including thromboembolism and anaphylaxis (risk ratio 1.09 [0.88 - 1.35]), acute transfusion reactions (risk ratio 0.96 [0.75 - 1.24]), or other adverse events (risk ratio 1.01 [0.97 - 1.05]) when compared to untreated platelets.16,17 The storage solutions (PAS or plasma) used and the method of platelet collection (apheresis or pooled) varied between included studies. After the most recent Cochrane review in 2017, a randomized trial of pathogen-reduced platelets and untreated platelets in PAS, compared to untreated platelets in plasma, reported a higher rate of allergic transfusion reactions among untreated platelet product.40 National hemovigilance data from Switzerland of over 200,000 INTERCEPT platelet concentrates (2011-2016) showed a similar safety profile and observed a reduction in life-threatening and fatal reactions as well as in high-imputability reactions when pathogen-reduced platelets were implemented.18 The authors note that this correlated with fewer allergic transfusion reactions, likely due to the lower plasma content of pathogen-reduced platelets. A prospective hemovigilance study in 11 European countries of INTERCEPT platelets over 7 years reported an excellent safety profile, comparable to untreated platelet products.17

From a respiratory risk perspective, an early randomized controlled trial (SPRINT) which randomized 645 patients with thrombocytopenia to INTERCEPT or untreated platelet transfusions, suggested a risk of ARDS (5/318 INTERCEPT versus 0/327 untreated). Secondary analysis of the data revealed no differences between the two groups.41 More recently, the PIPER trial, a phase IV post-market surveillance study, evaluated platelet transfusions in hematology-oncology patients at 15 U.S. sites. The study included 2,291 patients (9% were less than 18 years of age) over 10,000 platelet transfusions and reported no difference in treatment-emergent assisted mechanical ventilation or pulmonary injury between pathogen-reduced versus untreated platelets. No significant difference was detected for ARDS or other adverse events.42 Swiss hemovigilance data have also failed to detect a difference, reporting a TRALI risk of 1:31,000 for untreated and 1:33,000 for pathogen-reduced platelets.43

Previously published randomized trials have included small numbers of pediatric patients.44-47 The safety and efficacy of pathogen-reduced platelets have been better studied in pediatric patients48-52 in retrospective and hemovigilance studies.53 Schulz and colleagues reported a safety monitoring assessment on the use of pathogen-reduced platelets in a cohort of 1,932 platelet transfusions (45% untreated 55% pathogen-reduced) among 240 pediatric patients, including NICU patients.49 No differences in adverse events, transfusion reactions, and red cell transfusions were reported. A multinational study of over 3,800 pediatric patients who received over 7,900 platelet transfusions over 7 years reported no increases in adverse transfusion reactions compared to conventional platelets, and a reduced incidence of allergic transfusion reactions.48 French national hemovigilance data of over 1,000 neonatal and pediatric patients have similarly suggested safety of pathogen-reduced platelets among pediatric patients.53

Inactivates white blood cells

The inhibition of leukocyte replication and cytokine production is also an important benefit of the pathogen-reduction because it simplifies platelet inventory management and ordering. Because amotosalen treatment prevents T cell proliferation, irradiation to prevent Ta-GVHD is not needed for pathogen-reduced components.54 Similarly, cytomegalovirus (CMV)-negative blood components (currently restricted to use in intrauterine transfusions only) are not required because pathogen-reduced platelets are considered CMV-negative.55 For more on reducing the risk of transfusion-transmitted CMV, see the National Advisory Committee on Blood and Blood Products recommendations and education document.

Inventory changes

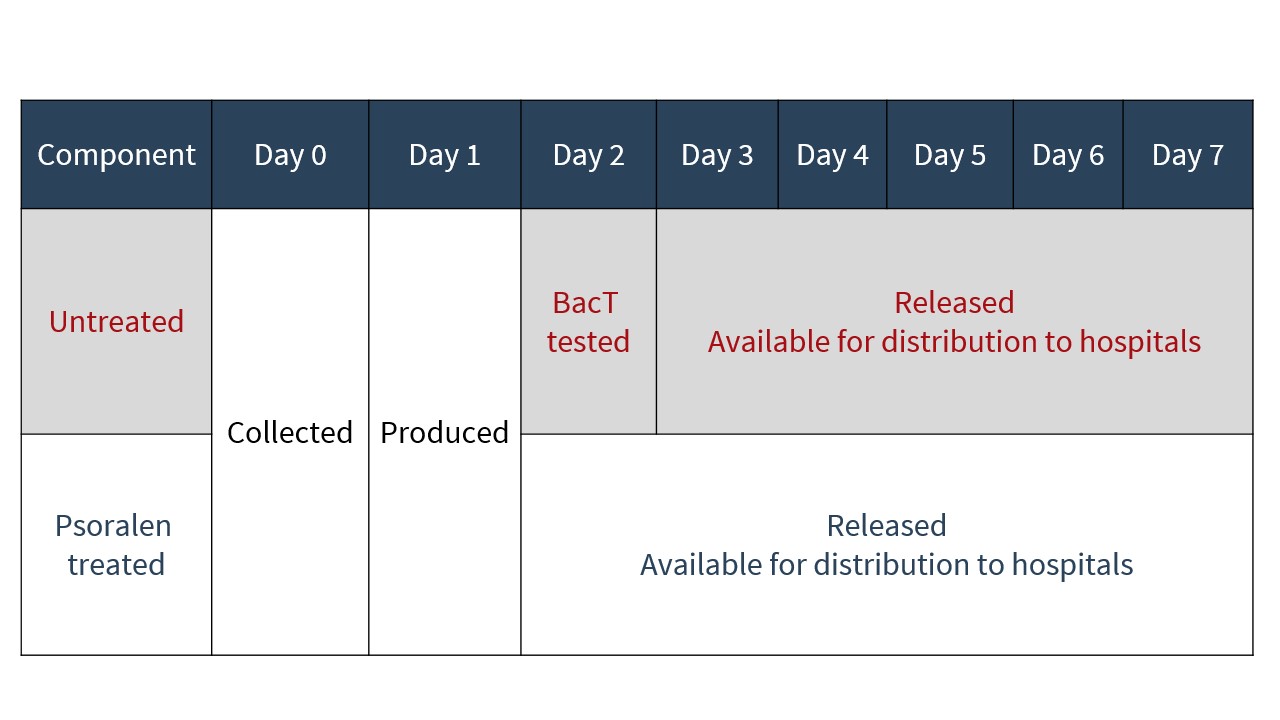

As PIT eliminates the need for platelets to undergo bacterial testing, as is currently performed on untreated platelets, pathogen-reduced platelets are issued to hospitals approximately 24 hours earlier in their shelf life than untreated platelets (see Figure 4).

Drawbacks

Platelet count increment and transfusion requirements

The majority of clinical trials using pathogen-reduced platelets focused on the hematology-oncology adult patient population. Of the trials examining the INTERCEPT system, platelet product types (e.g., plasma only, PAS, different formulations of PAS, pooled platelets, apheresis platelets) and plate product yields varied between studies. Overall, there was a statistically significant reduction in corrected count increment at 1 hour and 24 hours, an increase in the number of platelet transfusions, and a shorter time interval between transfusions for patients who received pathogen-reduced platelets compared those who received untreated platelets.16,40,42 These differences, however, were small. In a 2017 Cochrane review, the mean difference in number of platelet transfusions required per patient was 1.30 (95% CI 0.84 to 1.77, p<0.001, I2=49%). Differences in 24 hour corrected count increment and time interval between transfusions were a mean difference of -3.5 (95% CI -4.18 to -2.82, p<0.0001, I2=0%) and a mean difference of -0.50 days (95% CI -0.61 to -0.38, p<0.001, I2=0%), respectively. Crucially, there were no detectable differences in clinically significant bleeding (Grade 2 WHO bleed or greater) when pathogen-reduced and untreated platelets were compared.16 The decreased platelet count increment was thought to be multifactorial, resulting from a reduced platelet count per transfused unit and increased platelet activation during manufacturing.56

Platelet refractoriness

Platelet refractoriness, defined variably in clinical trials, has been reported to be more common among patients transfused with pathogen-reduced platelets compared to untreated platelets. The question of whether refractoriness is due to non-immune causes or alloimmunization remains incompletely understood.57 Previous small studies suggested that pathogen-reduced platelets may increase alloimmunization risk.16However, a large randomized controlled trial (SPRINT), which randomized 645 patients with thrombocytopenia to INTERCEPT or untreated platelet transfusions, detected no significant differences in HLA alloimmunization or platelet-specific antibodies between the study arms, despite the INTERCEPT arm requiring more platelet transfusions.44 Furthermore, among patients who developed refractoriness, lymphocytoxic antibodies were significantly more common in the group transfused with untreated platelets. A secondary analysis of the Italian Platelet Technology Assessment Study (IPTAS) randomized trial was insufficiently powered to address this question. Patients were assessed for the presence of HLA antibodies prior to and following platelet transfusion with either pathogen-reduced or untreated platelets. No statistically significant differences were observed in the rates of HLA alloimmunization.58 Overall, evidence to date suggests that refractoriness following pathogen-reduced platelet transfusion is most consistent with non-immune causes and can likely be overcome with additional platelet transfusions.

Amotosalen hypersensitivity and activation from some phototherapy devices

Pathogen-reduced platelets are contraindicated for patients with a history of hypersensitivity reactions to amotosalen or other psoralen products. The product is also contraindicated in neonates treated with phototherapy devices that emit a peak energy wavelength of less than 425 nm or lower bound of the emission bandwidth of less than 375 nm due to the potential for erythema resulting from the interaction between UV light and amotosalen. Phototherapy with blue-green light with peak of 450-460nm is the current standard of care for treatment neonatal hyperbilirubinemia in Canada.59,60 In a small cohort of 11 patients, there were no instances of new rash associated with concomitant phototherapy (within the recommended wavelength parameters) and pathogen-reduced platelet transfusion.49,61

Paucity of long-term outcomes in neonatal and intrauterine transfusions

Since the approval of INTERCEPT treated platelets internationally, several studies have described the safety of these products in neonatal cohorts. Amato et al. evaluated 91 pediatric patients (<18 years old) and neonates (<30 days old) without any indication of harm.62 Schulz et al. assessed neonatal intensive care unit patients, infants aged 0–1 year not in the neonatal intensive care unit, and children aged 1–18 years. This study also found no harm to these patients.49 Lasky et al. reviewed 191 neonatal and pediatric patients receiving 1,010 platelet transfusions, of which 37 neonates were transfused with INTERCEPT platelets and 68 patients received only INTERCEPT treated platelets.52 There were no increases in adverse events compared with untreated platelets, including those that received phototherapy. Delaney et al. reported on 1,188 patients under 4 months who received pathogen-reduced platelets without issue. Short-term safety data have demonstrated safety among neonates, but long-term data are currently limited. There is no published evidence for the use of INTERCEPT platelets for intrauterine platelet transfusions, for which untreated platelets will remain available. Pathogen-reduced platelets are an alternative platelet product in situations when the benefit outweighs the risk (e.g., emerging pathogen crisis). Benefit and risks should be assessed and balanced before using pathogen-reduced platelet in these settings.

Additional resources

Platelet component inventory, indications & ordering

- This one-page PDF summarizing available platelet types, indications and ordering information may be downloaded and printed.

665.15 KB

FAQ: Information for health professionals on pathogen-reduced platelets (PPPT)

- This FAQ addresses questions regarding PPPT components, including administration and clinical use.

FAQ: Information for health professionals on apheresis platelet psoralen-treated (APPT) and untreated apheresis platelet in PAS-E

- This FAQ has been developed to assist hospitals in implementing apheresis platelet psoralen-treated (APPT) and untreated apheresis platelet in PAS-E. These components are being implemented in Ottawa on June 12, 2023, with a national implementation to follow.

(Slide deck) Pathogen-reduced platelets: Clinical overview

- This slide deck may be downloaded for use in presentations. It provides health-care professionals with an overview of pathogen-reduced platelets, including pathogen inactivation technology, manufacturing, characteristics, and safety.

(Slide deck) Pathogen-reduced platelets: Clinical highlights

- This slide deck may be downloaded for use in presentations. It provides health-care professionals with a shorter version of the clinical overview presentation, highlighting key points about pathogen-reduced platelets.

(Slide deck) Pathogen-reduced platelets: Component overview

- This slide deck may be downloaded for use in presentations. It provides health-care professionals with an overview of hospital implementation considerations for pathogen-reduced platelets, including photos and descriptions of APPT and PPPT components and labels.

Visual inspection tool

The Visual Inspection Tool is a bench-level tool that depicts variation in the typical appearance of blood components. It was developed for all personnel in the hospital setting who handle blood components for transfusion and, as no two blood components will look exactly the same, should be used in conjunction with other required protocols or work instructions for the visual inspection of components. The Visual Inspection Tool replaces the Visual Assessment Guide.

For more information on pathogen-reduced pooled platelets, visit the OrbCon (Ontario Regional Blood Coordinating Network) website to view or download resources developed by Dr. Jeannie Callum, director of Transfusion Medicine at Kingston Health Sciences Centre and affiliate scientist at Canadian Blood Services.

Continuing professional development credits

Fellows and health-care professionals who participate in the Canadian Royal College's Maintenance of Certification (MOC) program can claim the reading of the Clinical Guide to Transfusion as a continuing professional development (CPD) activity under Section 2: Individual learning. Learners can claim 0.5 credits per hour of reading to a maximum of 30 credits per year.

Medical laboratory technologists who participate in the Canadian Society for Medical Laboratory Science’s Professional Enhancement Program (PEP) can claim the reading of the Clinical Guide to Transfusion as a non-verified activity.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Michelle Zeller, MD,FRCPC, MHPE, DRCPSC; Anita Howell, BSc, MLT; Ken McTaggart, MSc, PEng; Peter Schubert, PhD, and Baia Lasky, MD; for their review of this chapter.

Suggested citation

Blais-Normandin I, Tordon B, Anani W, Ning S. Pathogen-reduced platelets. In: Khandelwal A, Abe T, editors. Clinical Guide to Transfusion [Internet]. Ottawa: Canadian Blood Services, 2022 [cited YYYY MM DD]. Chapter 19. Available from: https://professionaleducation.blood.ca

If you have questions about the Clinical Guide to Transfusion or suggestions for improvement, please contact us through the Feedback form.

References

- O'Brien, S. Surveillance Report 2020. (Canadian Blood Services, 2020).

- Ciaravi, V., McCullough, T. & Dayan, A.D. Pharmacokinetic and toxicology assessment of INTERCEPT (S-59 and UVA treated) platelets. Hum Exp Toxicol 20, 533-550 (2001).

- Canadian Blood Services. Circular of information for the use of human blood components - pathogen reduced platelet concentrates. (Canadian Blood Services, Ottawa, 2022).

- McDonald, C.P. Interventions Implemented to Reduce the Risk of Transmission of Bacteria by Transfusion in the English National Blood Service. Transfusion medicine and hemotherapy : offizielles Organ der Deutschen Gesellschaft fur Transfusionsmedizin und Immunhamatologie 38, 255-258 (2011).

- Ramirez-Arcos, S., Evans, S., McIntyre, T., et al. Extension of platelet shelf life with an improved bacterial testing algorithm. Transfusion 60, 2918-2928 (2020).

- Dodd, R.Y. Bacterial contamination and transfusion safety: experience in the United States. Transfus Clin Biol 10, 6-9 (2003).

- Cerus Corporation. INTERCEPT Blood System for Platelets and Plasma Pathogen Reduction System. (2021).

- Salunkhe, V., van der Meer, P.F., de Korte, D., et al. Development of blood transfusion product pathogen reduction treatments: a review of methods, current applications and demands. Transfusion and apheresis science 52, 19-34 (2015).

- Irsch, J. & Lin, L. Pathogen Inactivation of Platelet and Plasma Blood Components for Transfusion Using the INTERCEPT Blood System™. Transfusion medicine and hemotherapy : offizielles Organ der Deutschen Gesellschaft fur Transfusionsmedizin und Immunhamatologie 38, 19-31 (2011).

- Grass, J.A., Hei, D.J., Metchette, K., et al. Inactivation of Leukocytes in Platelet Concentrates by Photochemical Treatment With Psoralen Plus UVA. Blood 91, 2180-2188 (1998).

- Li, M., Irsch, J., Corash, L., et al. Is pathogen reduction an acceptable alternative to irradiation for risk mitigation of transfusion-associated graft versus host disease? Transfusion and Apheresis Science 61(2022).

- Sim, J., Tsoi, W.C., Lee, C.K., et al. Transfusion of pathogen-reduced platelet components without leukoreduction. Transfusion 59, 1953-1961 (2019).

- Ciaravino, V., Hanover, J., Lin, L., et al. Assessment of safety in neonates for transfusion of platelets and plasma prepared with amotosalen photochemical pathogen inactivation treatment by a 1-month intravenous toxicity study in neonatal rats. Transfusion 49, 985-994 (2009).

- Ciaravino, V. Preclinical safety of a nucleic acid-targeted Helinx compound: a clinical perspective. Seminars in hematology 38, 12-19 (2001).

- Webert, K.E., Cserti, C.M., Hannon, J., et al. Proceedings of a Consensus Conference: pathogen inactivation-making decisions about new technologies. Transfusion medicine reviews 22, 1-34 (2008).

- Estcourt, L.J., Malouf, R., Hopewell, S., et al. Pathogen‐reduced platelets for the prevention of bleeding. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2017).

- Knutson, F., Osselaer, J., Pierelli, L., et al. A prospective, active haemovigilance study with combined cohort analysis of 19,175 transfusions of platelet components prepared with amotosalen-UVA photochemical treatment. Vox sanguinis 109, 343-352 (2015).

- Jutzi, M., Mansouri Taleghani, B., Rueesch, M., et al. Nationwide Implementation of Pathogen Inactivation for All Platelet Concentrates in Switzerland. Transfusion Medicine and Hemotherapy 45, 151-156 (2018).

- Canadian Blood Services. Circular of information for the use of human blood components - platelets. (Canadian Blood Services, Ottawa, 2022).

- van der Meer, P.F. & de Korte, D. Platelet Additive Solutions: A Review of the Latest Developments and Their Clinical Implications. Transfusion Medicine and Hemotherapy 45, 98-102 (2018).

- Tobian, A.A., Fuller, A.K., Uglik, K., et al. The impact of platelet additive solution apheresis platelets on allergic transfusion reactions and corrected count increment (CME). Transfusion 54, 1523-1529; quiz 1522 (2014).

- Cohn, C.S., Stubbs, J., Schwartz, J., et al. A comparison of adverse reaction rates for PAS C versus plasma platelet units. Transfusion 54, 1927-1934 (2014).

- van Hout, F.M.A., van der Meer, P.F., Wiersum-Osselton, J.C., et al. Transfusion reactions after transfusion of platelets stored in PAS-B, PAS-C, or plasma: a nationwide comparison. Transfusion 58, 1021-1027 (2018).

- Mertes, P.M., Tacquard, C., Andreu, G., et al. Hypersensitivity transfusion reactions to platelet concentrate: a retrospective analysis of the French hemovigilance network. Transfusion 60, 507-512 (2020).

- Mowla, S.J., Kracalik, I.T., Sapiano, M.R.P., et al. A Comparison of Transfusion-Related Adverse Reactions Among Apheresis Platelets, Whole Blood-Derived Platelets, and Platelets Subjected to Pathogen Reduction Technology as Reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network Hemovigilance Module. Transfusion medicine reviews 35, 78-84 (2021).

- Weisberg, S.P., Shaz, B.H., Tumer, G., et al. PAS-C platelets contain less plasma protein, lower anti-A and anti-B titers, and decreased HLA antibody specificities compared to plasma platelets. Transfusion 58, 891-895 (2018).

- Andreu, G., Boudjedir, K., Muller, J.-Y., et al. Analysis of Transfusion-Related Acute Lung Injury and Possible Transfusion-Related Acute Lung Injury Reported to the French Hemovigilance Network From 2007 to 2013. Transfusion medicine reviews 32, 16-27 (2018).

- KC, G., Murugesan, M., Nayanar, S.K., et al. Comparison of ABO antibody levels in apheresis platelets suspended in platelet additive solution and plasma. Hematology, Transfusion and Cell Therapy 43, 179-184 (2021).

- Pagano, M.B., Katchatag, B.L., Khoobyari, S., et al. Evaluating safety and cost-effectiveness of platelets stored in additive solution (PAS-F) as a hemolysis risk mitigation strategy. Transfusion 59, 1246-1251 (2019).

- Mathur, A., Swamy, N., Thapa, S., et al. Adding to platelet safety and life: Platelet additive solutions. Asian J Transfus Sci 12, 136-140 (2018).

- Bastos, E.P., Castilho, L., Bub, C.B., et al. Comparison of ABO antibody titration, IgG subclasses and qualitative haemolysin test to reduce the risk of passive haemolysis associated with platelet transfusion. Transfusion medicine 30, 317-323 (2020).

- Dunbar, N.M. Does ABO and RhD matching matter for platelet transfusion? Hematology / the Education Program of the American Society of Hematology. American Society of Hematology. Education Program 2020, 512-517 (2020).

- Balbuena-Merle, R., West, F.B., Tormey, C.A., et al. Fatal acute hemolytic transfusion reaction due to anti-B from a platelet apheresis unit stored in platelet additive solution. Transfusion 59, 1911-1915 (2019).

- de Wildt-Eggen, J., Nauta, S., Schrijver, J.G., et al. Reactions and platelet increments after transfusion of platelet concentrates in plasma or an additive solution: a prospective, randomized study. Transfusion 40, 398-403 (2000).

- Kerkhoffs, J.-L.H., Eikenboom, J.C., Schipperus, M.S., et al. A multicenter randomized study of the efficacy of transfusions with platelets stored in platelet additive solution II versus plasma. Blood 108, 3210-3215 (2006).

- Tardivel, R., Vasse, J., Gaucheron, S., et al. A comparative study of the efficiency of plasma and additive solution preserved platelets. Vox sanguinis 103(2012).

- Benjamin, R.J., Braschler, T., Weingand, T., et al. Hemovigilance monitoring of platelet septic reactions with effective bacterial protection systems. Transfusion 57, 2946-2957 (2017).

- Cloutier, M., De Korte, D. & ISBT Transfusion-Transmitted Infectious Diseases Working Party, S.o.B. Residual risks of bacterial contamination for pathogen-reduced platelet components. Vox sanguinis 117, 879-886 (2022).

- Domanović, D., Ushiro-Lumb, I., Compernolle, V., et al. Pathogen reduction of blood components during outbreaks of infectious diseases in the European Union: an expert opinion from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control consultation meeting. Blood transfusion = Trasfusione del sangue 17, 433-448 (2019).

- Garban, F., Guyard, A., Labussière, H., et al. Comparison of the Hemostatic Efficacy of Pathogen-Reduced Platelets vs Untreated Platelets in Patients With Thrombocytopenia and Malignant Hematologic Diseases: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncology 4, 468-475 (2018).

- Snyder, E., McCullough, J., Slichter, S.J., et al. Clinical safety of platelets photochemically treated with amotosalen HCl and ultraviolet A light for pathogen inactivation: the SPRINT trial. Transfusion 45, 1864-1875 (2005).

- Snyder EL, W.A., Refaai MA, Cohn CS, Poisson J, Fontaine MJ, Nooka A, Uhl L, Spinella P, Corash L. The PIPER phase 4 study: pathogen inactivated platelets entering routine practice. Oral abstract presented at: The AABB Annual Meeting (Virtual), 2021; Transfusion, 2021, Vol. 61, PL4-AM21-33.

- Amsler, L. & Jutzi, M. Haemovigilance annual report 2015. (Swissmedic, Swiss Agency for Therapeutic Products, Bern, Switzerland, 2016).

- McCullough, J., Vesole, D.H., Benjamin, R.J., et al. Therapeutic efficacy and safety of platelets treated with a photochemical process for pathogen inactivation: the SPRINT Trial. Blood 104, 1534-1541 (2004).

- Cazenave, J.P., Davis, K. & Corash, L. Design of clinical trials to evaluate the efficacy of platelet transfusion: the euroSPRITE trial for components treated with Helinx technology. Seminars in hematology 38, 46-54 (2001).

- Agliastro, R., De Francisci, G., Bonaccorso., R., et al. Clinical study in pediatric hemato-oncology patients: eLicacy of pathogen inactivated buLy coat platelets versus aphaeresis platelets Transfusion 46, 117A (2006).

- DeFrancisci, G., Bonaccorso, R., Bellavia, D., et al. Clinical trial on the use of pathogen inactivated platelets, with Helinx® technology, in cardio paediatric surgery and cirrhotic patients Transfusion 44, 17A (2004).

- Delaney M, B.J., Andrew J, et al,. Multinational analysis of transfusion reactions in children transfused with pathogen inactivated platelets. Oral abstract presented at: The AABB Annual Meeting (Virtual), 2021; Transfusion, 2021, Vol. 61, PL3-AM21-33.

- Schulz, W.L., McPadden, J., Gehrie, E.A., et al. Blood Utilization and Transfusion Reactions in Pediatric Patients Transfused with Conventional or Pathogen Reduced Platelets. The Journal of pediatrics 209, 220-225 (2019).

- Schulz WL, Gokhale A., McPadden J, et al. Transfusion of pathogen reduced vs conventional platelets in pediatric patients: An assessment of platelet usage and incidence of transfusion reactions. Abstract presented at: The AABB Annual Meeting, 2018; Boston, MA: Transfusion, 2018, Vol. 58 6A-254A.

- Jimenez-Marco, T., Garcia-Recio, M. & Girona-Llobera, E. Use and safety of riboflavin and UV light-treated platelet transfusions in children over a five-year period: focusing on neonates. Transfusion 59, 3580-3588 (2019).

- Lasky, B., Nolasco, J., Graff, J., et al. Pathogen-reduced platelets in pediatric and neonatal patients: Demographics, transfusion rates, and transfusion reactions. Transfusion 61, 2869-2876 (2021).

- Cazenave, J. & Isola, H. Pathogen Inactivation of Platelets. in Platelet Transfusion Therapy (eds. Sweeney, J. & Lozano, M.) 119-176 (AABB Press, Bethesda, MD, 2013).

- Cid, J. Prevention of transfusion-associated graft-versus-host disease with pathogen-reduced platelets with amotosalen and ultraviolet A light: a review. Vox sanguinis 112, 607-613 (2017).

- Lin, L. Inactivation of cytomegalovirus in platelet concentrates using Helinx technology. Seminars in hematology 38, 27-33 (2001).

- Snyder, E., Raife, T., Lin, L., et al. Recovery and life span of 111indium-radiolabeled platelets treated with pathogen inactivation with amotosalen HCl (S-59) and ultraviolet A light. Transfusion 44, 1732-1740 (2004).

- Stolla, M. Pathogen reduction and HLA alloimmunization: more questions than answers. Transfusion 59, 1152-1155 (2019).

- Norris, P.J., Kaidarova, Z., Maiorana, E., et al. Ultraviolet light-based pathogen inactivation and alloimmunization after platelet transfusion: results from a randomized trial. Transfusion 58, 1210-1217 (2018).

- Ebbesen, F., Donneborg, M.L., Vandborg, P.K., et al. Action spectrum of phototherapy in hyperbilirubinemic neonates. Pediatric research (2021).

- Barrington KJ, S.K., Canadian Paediatric Society, Fetus and Newborn Committee. Guidelines for detection, management and prevention of hyperbilirubinemia in term and late preterm newborn infants (35 or more weeks' gestation) - Summary. Paediatr Child Health 12, 401-418 (2007).

- Cerus. INTERCEPT® Blood System for Platelets - Package Insert – Large Volume (LV) Processing Set. (Cerus Corporation, Concord, CA, 2021).

- Amato, M., Schennach, H., Astl, M., et al. Impact of platelet pathogen inactivation on blood component utilization and patient safety in a large Austrian Regional Medical Centre. Vox sanguinis 112, 47-55 (2017).