Surveillance report 2021

We are pleased to present this annual report describing transmissible blood-borne infection surveillance. High quality and timely surveillance is central to the safety of the blood supply. This includes monitoring of transmissible disease markers that the blood is tested for (including bacteria) and investigation of any reports of possible transfusion transmission, as well as a horizon scan for any new pathogens that may pose a risk.

To request older Surveillance Reports, please contact us through the Feedback form.

Current issue - 2023

Surveillance Report 2021

Author: Sheila O'Brien, RN, PhD

Online publication date: October 2022

Executive summary

This annual report describes surveillance of transmissible blood-borne infections and emerging threats of concern. High quality and timely surveillance is central to the safety of the blood supply. This includes monitoring of transmissible disease markers that the blood is tested for and investigation of any reports of possible transfusion transmission, as well as a horizon scan for any new pathogens that may pose a risk. Non-infectious surveillance of aspects of donor health and safety as well as diagnostic services are also included.

Infectious risk monitoring

The most up-to-date tests for pathogens are used to identify infectious donations and prevent their release for patient use. In 2021, transmissible disease rates per 100,000 donations continued to be very low: 0.4 HIV, hepatitis C (HCV) 7.2, hepatitis B (HBV) 4.9, HTLV 1.0 and syphilis 6.7. Selective testing of donors at risk of Chagas disease identified 2 positive donations, and there were 9 donations positive for West Nile Virus (WNV). Residual risk estimates of a potentially infectious donation from a unit of blood are very low at 1 in 12.9 million donations for HIV, 1 in 27.1 million donations for HCV and 1 in 2.0 million donations for HBV. Lookback and traceback investigations did not identify any transfusion transmitted infections. Bacterial growth was identified in 171 platelet products. Of 452 potential peripheral blood stem cell or bone marrow donors tested, 1 was positive for hepatitis C. Of 424 samples from mothers donating stem cells collected from the umbilical cord and placenta (called “cord blood”) after their babies were born, 1 was positive for HTLV.

Horizon scanning for emerging pathogens monitors potential threats to safety. Risk of a tick-borne disease, babesiosis, continues to be monitored. The parasite (Babesia microti) that causes babesiosis appears to be in the early stages of becoming established in a few places in Canada, especially in Manitoba. Travelers and former residents from malaria risk areas are temporarily deferred for malaria risk. In addition, a 3 week deferral for any travel outside Canada, the USA and Europe reduces risk from short term travel related infections, such as Zika virus. In 2020 this was extended to include any travel outside of Canada for 2 weeks to reduce risk of exposure to COVID-19 to other donors and staff and continued over 2021.

COVID-19

A novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) was identified in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China in November 2019. On March 11th, 2020, the World Health Organization declared a COVID-19 pandemic. SARS-CoV-2 is not transmissible by blood but to keep donors, volunteers and staff safe numerous changes were made in the blood collection environment. Canadian Blood Services has tested over 290,000 blood samples since May 2020 for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in collaboration with the COVID-19 Immunity Task Force commissioned by the Canadian Federal Government. Seroprevalence to natural infection increased from less than 2% in January 2021 to about 5% of donors by November, then about 6% in December as a new variant, Omicron, became established. Vaccine related antibodies increased from about 2% to about 98% of donors over 2021, consistent with wide scale vaccination programs. These results were very important for Public Health officials to plan safety interventions for Canadians.

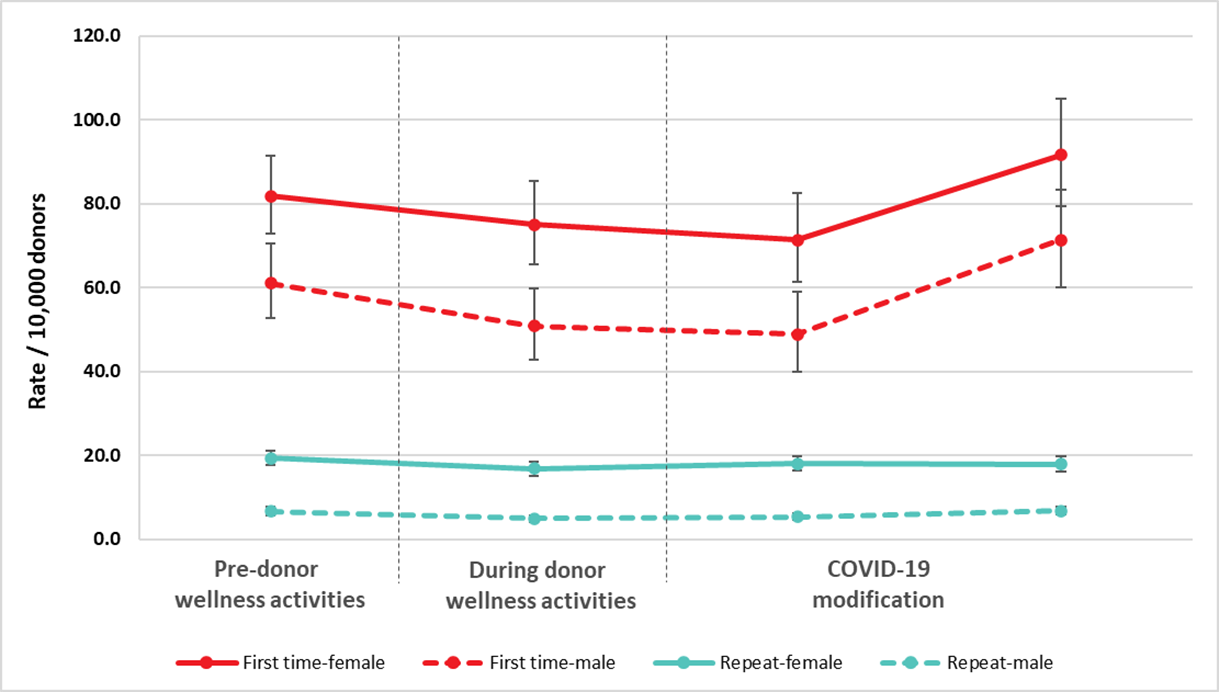

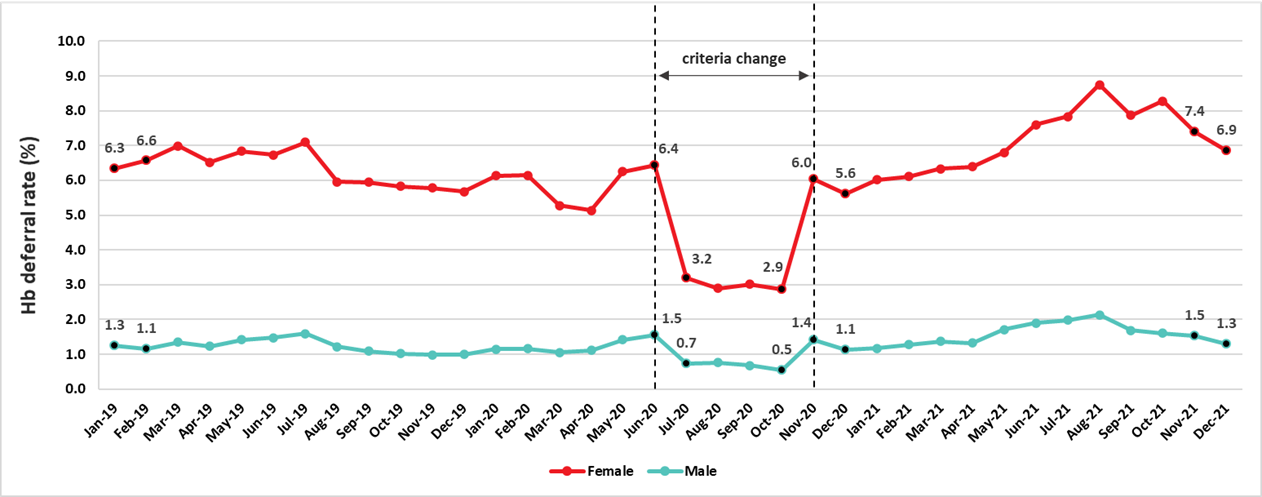

In 2020 Canadian Blood Services quickly put in place measures to reduce risk to donors, volunteers and staff, and to ensure adequacy of the blood supply. Giving blood is very safe, and serious reactions in donors are quite rare. A Donor Wellness initiative was implemented in March 2019 which reduced vasovagal (pre-faint and faint) reactions and helped donors to feel well after donating. To reduce points of contact that may be a risk for COVID-19 transmission (eating and consuming fluids on the donation site), these were modified with first-time donor vasovagal reaction rates rebounding to pre-Donor Wellness rates. To reduce deferrals and ensure adequacy of the blood supply if donor attendance dropped during the pandemic from July to October 2020 the minimum hemoglobin required to donate was reduced from 125 g/L to 120 g/L for women and from 130 g/L to 125 g/L for men. The deferrals related to low hemoglobin decreased from 7% to 3.2% for females and from 1.5% to 0.8% for males during that period, but over 2021 deferrals increased for both males and females, and in females remained elevated in December.

Diagnostic services laboratories

The Diagnostic Services Laboratories at Canadian Blood Services provide prenatal testing for some pregnant women, including all pregnancies in several provinces, and for some patients with complex transfusion needs. In 2021 1,101 red blood cell antibodies were identified in pregnant patients that may pose a risk of hemolytic disease of the fetus/newborn and 2,165 red cell antibodies were identified in patients who may need special matching for transfusion.

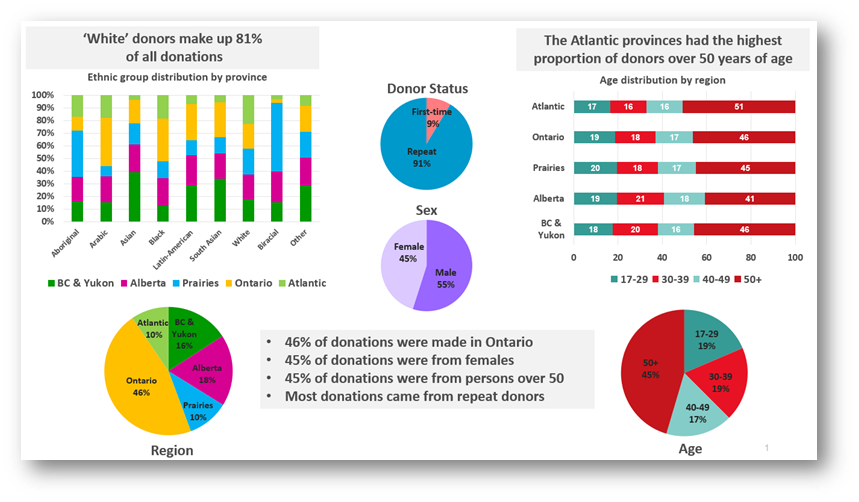

Donor demographics

Nearly a fifth of donations are from racialized donors. Most donations are repeat donations, a little more than half from males, nearly half (45%) from persons over 50 years of age. Nearly half (46%) of donations are from Ontario.

1. Introduction

Safety of the blood supply from pathogens involves a multifaceted approach. Donor education materials on the internet and required reading just before donating explain risk factors for transmissible infections and who should not donate. Before donating blood, everyone must complete a health history questionnaire which includes questions about specific risk factors for transmissible infections. This is followed by an interview with trained staff to decide if the person is eligible to donate blood. All donations are tested for markers of transfusion transmissible agents including HIV, HBV, HCV, human T-cell lymphotropic virus (HTLV) (a rare cause of leukemia) and syphilis. WNV testing is done during the at-risk period of the year (spring, summer and fall) and in at-risk travelers during the winter. In addition, donors at risk of Chagas disease (which is transmitted by the bite of an insect in Latin America) are tested, and platelet products are tested for bacteria. A new coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, which causes the respiratory infection, COVID-19, emerged in 2020 but it is not transmitted by blood transfusion. It continued to cause infections throughout 2021 with an impact on operational issues to ensure safety for donors, staff and volunteers while meeting the needs of blood recipients. Additionally, epidemiologic data on the frequency of antibodies in our donor population over time provided support for public health decision making during the pandemic.

Surveillance includes monitoring of transmissible infection testing in donors, investigation of possible transfusion transmitted infections in recipients and horizon scanning for new, emerging pathogens. Monitoring the safety of donors is also essential. Although surveillance is conducted in "real time" over each year, final verification steps generally impose a short delay in producing a final report. Surveillance also includes monitoring of donor safety. This report describes Canadian Blood Services’ approach to surveillance of transmissible blood-borne infection, infectious threats and donor safety, as well as data for the calendar year of 2021.

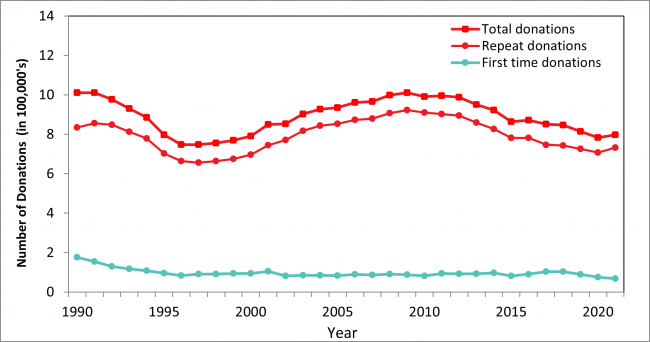

2. Blood donor surveillance

The numbers of allogeneic blood donations (whole blood and platelet and plasma apheresis) from first time and repeat donors are shown in Figure 1. The majority of donations are from repeat donors (91.7%). The proportion of donations from first time donors continues to decrease from 12.3% in 2018, to 11.1% in 2019 to 9.8% in 2020 to 8.3% in 2021.

Note: Source plasma donations are not included.

The “Classical” pathogens

Details of screening tests used, and dates of implementation are shown in Appendix I. In Table 1 the numbers of positive donations and the rates of positive tests per 100,000 donations are shown for 2021 by demographic groups. When a transmissible infection is detected, it is most often in a first-time donor as these donors have not been tested previously and may have acquired the infection at any time in their lives. All transmissible infection positive donations occurred in whole blood donations. There were 3 HIV positive donations in 2021. In the past 5 years the number of HIV positive donations has ranged from 0 to 4 per year. The rate per 100,000 donations has decreased for most markers and the rate for repeat donations is extremely low (see Appendix II). The exception is syphilis which has increased in 2021 from 4.1 per 100,000 donations in 2019 to 9.8 in 2020 and was still elevated in 2021 at 6.7 per 100,000. Syphilis cases have been increasing in the general population but are not directly comparable because public health cases only include people who had reason to be tested (usually new infections with symptoms) whereas blood donors include both people unaware of their infection and those who may have been infected in the past. It is unlikely that syphilis could be transmitted by transfusion due to modern blood processing methods.

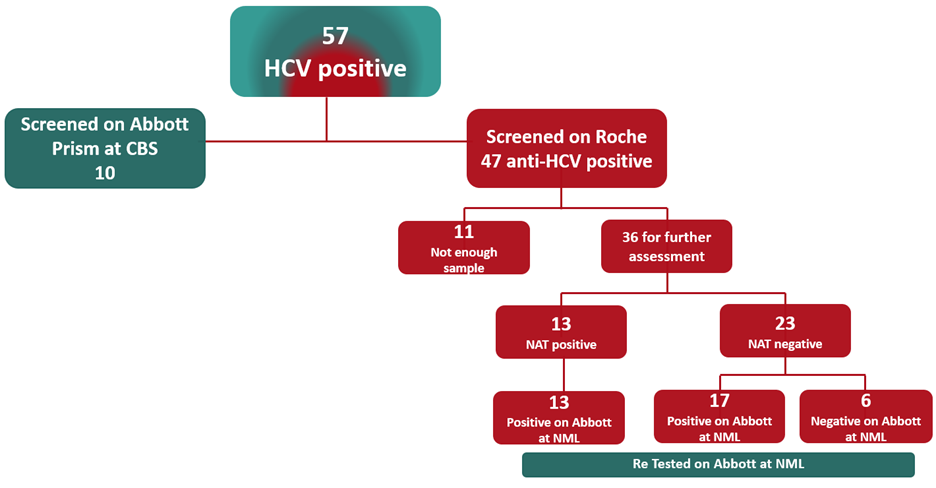

In April 2021 the serologic testing assay was changed and an increase in HCV positive donations was observed. These donations were re-tested on the prior assay and nearly all considered likely true positive. About 16% would have been negative on the prior assay. Importantly, all donations with detectable HCV nucleic acid were reactive on both assays, but the new assay could be detecting low level antibodies from older infections that were resolved.

For details see Appendix III

Table 1: Confirmed positive donations and prevalence rates per 100,000 donations in 2021

| Characteristic | Number of Donations | Percent of Donations | HIV | HCV | HBV | HTLV | Syphilis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pos | Rate | Pos | Rate | Pos | Rate | Pos | Rate | Pos | Rate | |||

| Donor status | ||||||||||||

|

First time |

66,297 | 8.3 | 2 | 3.0 | 45 | 67.9 | 38 | 57.3 | 7 | 10.6 | 37 | 55.8 |

|

Repeat |

731,193 | 91.7 | 1 | 0.1 | 12 | 1.6 | 1 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.1 | 16 | 2.2 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

|

Female |

347,462 | 43.6 | 0 | - | 26 | 7.5 | 9 | 2.6 | 3 | 0.9 | 16 | 4.6 |

|

Male |

450,028 | 56.4 | 3 | 0.7 | 31 | 6.9 | 30 | 6.7 | 5 | 1.1 | 37 | 8.2 |

| Age | ||||||||||||

|

17-29 |

144,730 | 18.2 | 1 | 0.7 | 8 | 5.5 | 5 | 3.5 | 2 | 1.4 | 17 | 11.8 |

|

30-39 |

149,546 | 18.8 | 1 | 0.7 | 11 | 7.4 | 12 | 8.0 | 1 | 0.7 | 16 | 10.7 |

|

40-49 |

135,047 | 16.9 | 1 | 0.7 | 12 | 8.9 | 11 | 8.2 | 1 | 0.7 | 7 | 5.2 |

|

50+ |

368,167 | 46.2 | 0 | - | 26 | 7.1 | 11 | 3.0 | 4 | 1.1 | 13 | 3.5 |

| Total | 797,490 | 100 | 3 | 0.4 | 57 | 7.2 | 39 | 4.9 | 8 | 1.0 | 53 | 6.7 |

All transmissible infection positive donations are destroyed. The main source of risk is when a blood donor acquired the infection too recently to be detected by testing. This is called the “window period” of infection. With current testing the window period is very short. For HIV and HCV an infection would be detected within 1 to 2 weeks of a donor being infected by nucleic acid testing (NAT) and for HBV within one month. The residual risk of infection is the estimated risk of a potentially infectious donation being given during the “window period”. These estimates, shown in Table 2 are based on new infections (positive donations with a prior donation which tested negative within the last 3 years) and include 2018 -2020 data. The risk is currently extremely low, but of course it can never be zero.

Table 2: Estimated residual risk of HIV, HCV and HBV

| HIV | HCV | HBV |

|---|---|---|

| 1 in 12.9 million donations | 1 in 27.1 million donations | 1 in 2.0 million donations |

Risk factors

Risk factor interviews are carried out with donors who test positive for transmissible infections. The main risk factors are shown in Table 3. HIV infections are very rare in donors; therefore it is difficult to generalize the risk factors. It should be noted that participation is voluntary and therefore there are only data for some donors, and that for many donors no risk factors were identified..

Table 3: Risk factors for infectious disease in blood donors

| Infection | Risk Factor |

|---|---|

| HIV | High risk heterosexual partners Male to male sex |

| HCV |

History of intravenous drug use |

| HBV | Born in a higher prevalence country |

| HTLV | Born overseas (especially Caribbean) History of other sexually transmitted disease History of blood transfusion |

| Syphilis | Previous history of syphilis |

Note: Not all donors are available/willing to be interviewed.

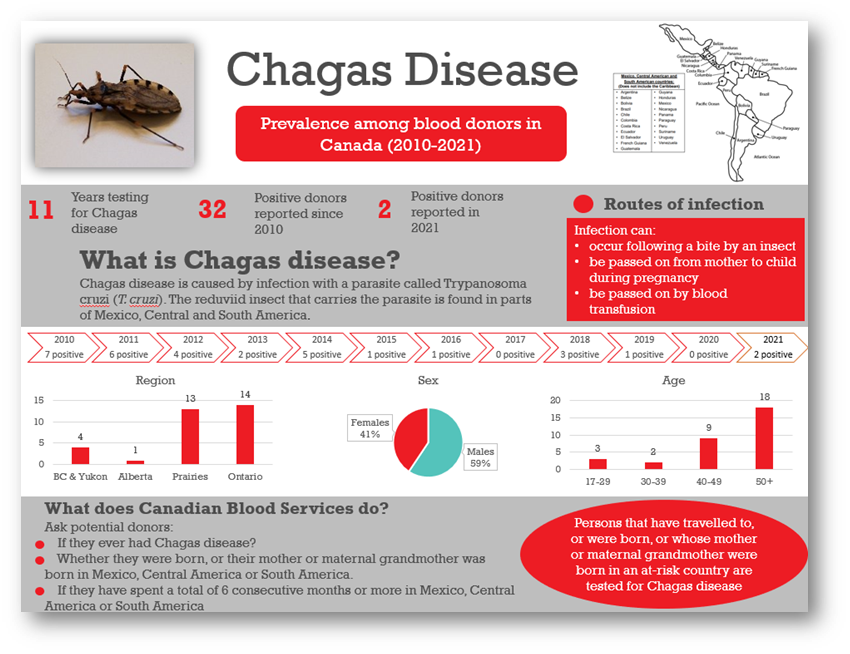

Chagas disease (Trypanosoma cruzi)

Chagas disease is caused by infection with a parasite called Trypanosoma cruzi (T. cruzi). People can become infected with it after being bitten by an insect found in parts of Mexico, Central and South America. The T. cruzi parasite can also be passed on from mother to child during pregnancy and by blood transfusion. Since Canadian Blood Services implemented testing of at-risk donors in 2010, 32 T. cruzi positive donations have been identified (see Figure 2). There were 2 positive donations in 2021 of 7,268 tested.

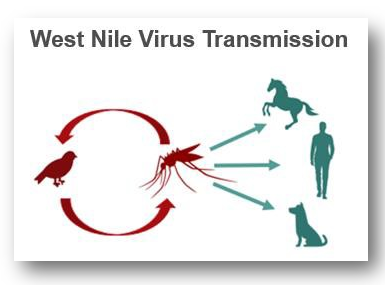

West Nile virus

West Nile virus is a mosquito-borne virus that has been present in North America since 1999 (in Canada since 2002). Although symptoms can be severe, they are usually mild, and most people are not aware of their infection. During spring, summer and fall, donations are routinely tested in mini-pools of 6 donations. However, to further reduce the risk, an algorithm is applied to identify all donations from areas where West Nile virus is active, and these are tested as single donations. In 2021, 396,950 donations were tested over the spring/summer/fall when all donations were tested, and 9 donations were positive, identified from August 17 to September 29. Eight positive donations were from Ontario and 1 from Manitoba corresponding with the location of clinical cases. With only travelers tested over the winter, 4,935 donations (from Jan 1 to May 30, 2021, and November 28 to December 31, 2021) were tested and none found to be positive.

3. Surveillance for emerging pathogens

A horizon scan of potential blood borne infections in the general community ensures rapid revision of donor policies to maintain safety. Even before a new infectious disease is reported in Canada, we are aware of emerging infectious agents by monitoring outbreaks in other parts of the world. Although international travel was reduced during the COVID-19 pandemic it is otherwise commonplace, and infections can rapidly enter from other countries. To ensure that potential risks are identified, Canadian Blood Services needs to be connected with the latest infectious disease information at all times. Canadian Blood Services’ medical and scientific staff participate in public health and infectious disease professional organizations and monitor web sites and journals where new information is posted. When appropriate the Alliance of Blood Operators (ABO) Risk Based Decision Making Framework can be used to facilitate policy decision making. This ensures that relevant assessments including infectious risk to recipients, operational impact of strategies, stakeholder input and health economics are considered. A range of infectious agents that could emerge as a threat within Canada are being monitored.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)

SARS-CoV-2 is a novel coronavirus first identified in Wuhan, Hubei province of China in late 2019. It is responsible for a severe respiratory illness known as the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Some people become extremely ill and can die from complications, while others experience mild symptoms and may not be aware of their infection. On March 11th, 2020, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 to be a pandemic. Since then, over 2.1 million Canadians have received a COVID-19 diagnosis and over 30,000 people have died. SARS-CoV-2 is not transmissible by blood transfusion; however it did impact on procedures for ensuring donor safety and blood collection. For details see Section 8.

SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) seroprevalence

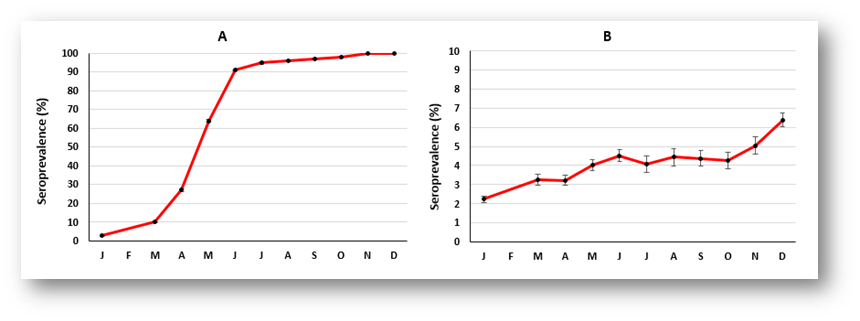

Early in the pandemic with less than 500 confirmed cases across Canada (March 23rd, 2020), strict physical distancing measures were implemented in most provinces. As a result, the first wave of the epidemic peaked by the end of April and plateaued in July and August. A resurgence of cases began in late September 2020, peaking in January 2021 (the second wave). This was followed by a third wave that emerged in many regions across Canada in March 2021, which then subsided in late April. A fourth wave of this epidemic began in early August 2021 and subsided by the end of October. In mid-December 2021, a fifth wave began. Vaccination of Canadians began in December 2020 and was rolled out over 2021 (2 shots). Antibody concentrations typically peak within a month of vaccination and then gradually decrease. Antibody concentrations can be much higher after a second or third dose of vaccine, or when an infection occurs pre- or post-vaccination. More than 86% of the eligible population had received two doses as of November 20, 2021. Starting in November 2021, some Canadians became eligible for a third dose.

Public health reported cases do not show the true infection rate because some infections will not cause illness, others may not be severe enough for people to seek testing, and testing may be disproportionately directed to outbreaks. Testing for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies is important to understand what proportion of the population have already been infected (the seroprevalence), what proportion have vaccine related antibodies and to monitor infection over the course of the pandemic. These data are used to improve mathematical models to predict the course of infection and inform public health policy. In partnership with the COVID-19 Immunity Task Force, Canadian Blood Services is testing residual blood for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. To date over 290,000 samples from across Canada have been tested for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, of which about 160,000 were in 2021. Over 2021 seroprevalence due to natural infections increased from about 1% to about 7% in the last week of December. Vaccination antibodies increased from about 2% in January to 90% in June and by December 98%. Figure 3 shows the changes over 2021.

Point estimates are indicated on the graph by approximately monthly intervals, bars represent 95% Confidence Intervals.

Worldwide, blood services have leveraged their operational capacity to inform public health. SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence remained low in Canada but there were significant variations by regions, racialized individuals, and socioeconomic factors. Canadian Blood Services is committed to continuing to play a pivotal role in helping authorities evaluate public health policies, monitor disparities and track antibody concentrations as long as needed.

New Brunswick cluster

Since March 2021 Canadian Blood Services has been in contact with the Canadian Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease Surveillance System, PHAC and New Brunswick Public Health (PHNB) which is investigating a neurological disease cluster in the Moncton-Acadian Peninsula region of New Brunswick. As of March 2022, the following information is publicly available. https://www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/departments/ocmoh/cdc/neuro_cluster.html

Of the 48 cases, none fulfilled the full criteria of the case definition. Only twenty-five out of 48 cases met the criteria for rapidly progressing dementia. Only 19 of those had at least four of the clinical features mentioned in the definition, which were verified directly by a physician. Out of those 19 cases, one case did not have those symptoms during the first 18-36 months of illness. One other case did not fulfil the criteria for supporting investigations (in MRI, EEG, and SPECT-CT) as an alternative diagnosis was provided. There was no evidence of a known prion disease in any of these cases. In the remaining 17 cases there was sufficient evidence for alternative diagnoses (or potential alternative diagnoses).

Canadian Blood Services continues to engage New Brunswick Public Health on this issue. New Brunswick Public Health provided CBS with information on 14 individuals with a self-reported donation and/or transfusion history. A modified lookback is being completed by Canadian Blood Services. Four issued red blood cell units were distributed to four different hospitals. All four issued units were transfused according to hospital Blood Transfusion Service records and recipient information was provided to CBS. This recipient information was relayed back to PHNB to in turn match with any other individuals on the full cluster line list that PHNB maintains. There is no evidence that blood was implicated as a mode of transmission with respect to the posited neurological syndrome.

Babesiosis

Babesiosis comes from the bite of the black-legged tick (Ixodes scapularis) which can transmit the parasite B. microti. Usually it causes mild flu-like symptoms, and many people are not even aware that they have had it. However, it can also be transmitted by blood transfusion, and infection in blood recipients can result in severe illness or death. To date babesiosis cases in the general population have been reported mainly in the Northeastern and Upper Midwest parts of the United States where more than 1,500 cases per year are reported. Cumulatively more than 200 infections in the United States are believed to have been acquired from a transfusion. In Canada there has been one case of transfusion transmitted babesiosis in 1998 from a donor who had travelled to the Northeast US. In Canada the parasite is found in small numbers of ticks. A 2013 study at Canadian Blood Services and Héma-Québec tested 13,993 blood donations and none were positive. In 2013 one non-donor infected from a tick bite in Canada was reported. Ongoing public health surveillance of ticks suggests no increase in risk, but a donor study was carried out in 2018 involving more donors. One of 50,752 samples tested from southerly areas across Canada was positive by B. microti nucleic acid testing (NAT, donated in Manitoba and indicating an active infection) and of 14,758 samples tested for antibody to B. microti, 4 in Southwestern Ontario were positive (but negative by NAT, indicating likely resolved infection at some time in the past). In 2019 a donor developed illness after donating and was diagnosed with B. microti infection, likely infected in southern Manitoba. No recipients were infected from the donation. The estimated risk of a clinically relevant infection being transmitted from a blood transfusion in Canada is very low at 0.08 per year (0 – 0.38) per year, or about 1 in 12.5 years. The ABO Risk Based Decision Making Framework was used to evaluate possible risk mitigation strategies. Further studies are planned to follow possible expansion of babesia species in Canada.

Travel related infections

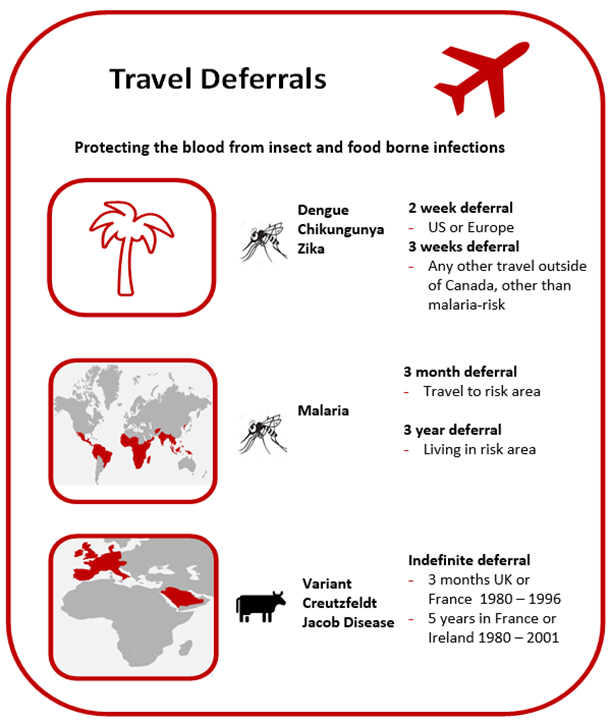

Donors who travel may return with infections that could be transmitted by blood (see Figure 4). Most are only at risk for a period of time after returning until the infection is eliminated from the donor’s bloodstream. Malaria risk is present in parts of the Caribbean, Mexico, Central and South America, Asia, and Africa. Donors are deferred after travel to risk areas for 3 months, enough time to develop symptoms. Former residents of endemic areas are deferred for 3 years because there is a chance they may be infected for a longer time period without symptoms. Other tropical mosquito-borne infections such as dengue virus have long been present in sunny destinations frequented by Canadians, but in recent years there have been outbreaks of others such as Chikungunya virus and Zika virus not previously seen in the Caribbean, Mexico, Central and South America. Risk to the blood supply was determined to be very low based on quantitative risk assessment. However, to address future travel risks, since 2016 Canadian Blood Services defers all donors who have travelled anywhere outside of Canada, the USA or continental Europe for 3 weeks after travel. By 2020 COVID-19 was circulating in Canada but travel-related infections were also of concern, especially new variants that may be rare in Canada. Although COVID-19 is not transfusion transmissible, in order to protect staff and other donors, a 2 week deferral for all travel outside of Canada was implemented. This includes travel to the US and Europe.

Residency or cumulative travel considered a risk for variant-Creutzfeldt Jakob disease (vCJD) result in permanent deferral. vCJD is acquired from eating infected meat (Bovine Spongiform Encephalitis, or BSE, known as “Mad Cow Disease”) in the UK, Western Europe or Saudi Arabia during the years of the BSE epidemic in cattle. Donors are deferred for time spent in those countries while infected meat may have been available. Infectious risks in other countries are closely monitored to decide if further action is needed.

4. Bacteria

Bacteria in blood products usually come from the skin of donors during their blood donation, although occasionally they may come from the donor’s bloodstream. The number of bacteria is usually very low, but because platelet products are stored at room temperature, bacteria can multiply to reach high concentrations and then pose a serious risk to the recipient. Canadian Blood Services tests all apheresis and pooled platelet products for bacteria using the BACT/ALERT System in which a sample from the product is inoculated into an aerobic (presence of oxygen) culture bottle and an anaerobic (absence of oxygen) culture bottle and monitored for growth for 7 days. If any bacterial growth is detected in the culture bottles, the product is not issued if it is still in inventory at Canadian Blood Services. If it has been sent to a hospital, it is recalled and returned to Canadian Blood Services from the hospital blood bank (i.e., has not been transfused or discarded). In 2021, 109,863 platelet products (17,450 apheresis and 92,413 pooled products) were tested, of which 112 apheresis and 374 pooled products had initial positive results for bacterial growth in the culture bottles. From these, 6 and 112 cultures were confirmed as true bacterial contaminations, for apheresis and pooled products, respectively. In addition, 6 apheresis and 47 pooled products with initial positive results were not confirmed as they were issued and/or transfused. This represents 171 products in total (15.6 per 10,000) with a chance of bacterial contamination with current testing, including both true positives and suspected positives.

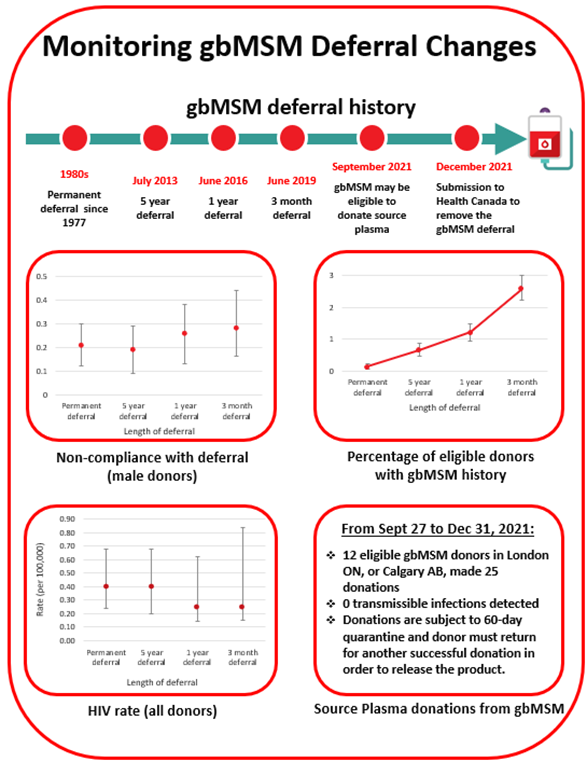

5. Donor eligibility criterion for male to male sex

In the 1980’s men who had sex with another man even once since 1977 were not eligible to donate blood to reduce the risk of HIV transmission. With much improved donor testing and surveillance for emerging pathogens the deferral period has been gradually reduced, moving to 5 years in 2013, to 1 year in 2016 and to 3 months in 2019. HIV rates did not increase following any of these changes (see Figure 5). Anonymous donor compliance surveys showed that shortening the deferral period allowed more gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (gbMSM) to donate blood and donor compliance was not adversely affected (see Figure 5). With the 3-month deferral in place the risk of releasing an HIV infectious unit for transfusion was very low at 1 in 19.9 million donations (1 in 2.7 million – 1 in 1,668 million).

gbMSM Research Grants

Canadian Blood Services is committed to ongoing revision of the gbMSM deferral policy. In 2017, Canadian Blood Services and Héma-Québec launched a competitive grant program to allocate funding provided by Health Canada to Canadian researchers to address the challenges in removing deferral criteria and ensuring the safety of the blood supply would be maintained. Fifteen research projects were funded by this grant program, of which two are still ongoing. In 2020, a second competitive grant program with funding provided by Health Canada focused on research related to plasma donation for gbMSM and four research projects were funded. These projects are still ongoing. For more information see: https://blood.ca/en/research/our-funded-research-projects?combine=msm

Plasma donation

In Canada, in September 2021, sexually active gbMSM became eligible to donate source plasma at two donation centres (London, Ontario and Calgary, Alberta) if they had not had a new sexual partner in the last three months, the donor and their partner had only had sex with each other in the last three months, and the donor met all the other criteria for donation. France has an apheresis-quarantined plasma program since 2016, which allows gbMSM to donate plasma if they have had only one sexual partner during the previous 4 months. In both Canada and France, plasma donated by gbMSM is stored until the donor returns to donate again 60 days after their donation and has another negative test. The product is then released. In France the plasma is used for transfusion. In Canada, the plasma is used to make plasma protein products, and as part of the processing, pathogen inactivation technology inactivates a broad spectrum of pathogens.

From September 27th to December 31st, 2021, there were 12 initial plasma donations from sexually active gbMSM who met the criteria, with seven donors returning to make further donations (25 donations). All donations tested negative for infectious disease markers and will become eligible for quarantine release if the donor returns to donate again after the 60-day period. More information about plasma eligibility can be found here: https://www.blood.ca/en/plasma/am-i-eligible-donate-plasma/men-who-have-sex-men

Individual behaviour based screening

Many countries have switched from lifetime to shorter time deferrals, and recently a number of countries have removed their time-based deferrals in favour of individual behaviour-based screening. The US currently has a 3-month deferral in place; the UK and the Netherlands removed their time-based deferral in 2021, and France recently announced removal of their deferral in 2022, all with different risk reducing steps. Canadian Blood Services initiated another compliance survey in late 2021 to further assess the impact of the 3-month deferral and evaluate comfort with being asked questions about sexual behaviours among all donors.

In December 2021, Canadian Blood Services submitted a proposal to the regulator, Health Canada, to remove the 3 month deferral for men having had sex with another man and instead focus on high-risk sexual behaviour among all donors.

6. Lookback/traceback

All cases of potential transfusion transmission of infections are investigated. The Lookback / Traceback Program is notified when a donor tests positive for a transmissible infection, or if the donor reports a transfusion transmissible infection after donating (even if it is not one that would normally be tested for). A Lookback investigation is initiated when previous or historical donations are identified, and hospitals are asked to contact the recipients of these donations to arrange testing. A traceback is initiated when a recipient is found to have a transmissible infection and transfusion was confirmed and it is queried as to whether their infection could have been from their blood transfusion. Hospitals provide a list of all blood products that the recipient received, and Canadian Blood Services attempts to contact the donors of these products to arrange testing unless current test results are available.

In 2021, there were 33 lookback cases that required investigation: 29 HCV, 2 HIV, 1 HBV, 1 HTLV. 26 of these were from donors who had a positive transmissible disease marker and 7 were from external testing or public health notification. Of these, 28 cases were closed (all recipients that could be contacted were tested). The remaining 5 cases were still open. There were 18 cases from previous years closed in 2021. No closed cases were associated with transfusion transmission.

There were 13 traceback cases that required investigation received from external sources in 2021 (12 HCV, 1 HBV). Of these, 11 cases were closed (all donors that could be contacted were tested), and 2 remain open. There were 16 cases from previous years closed in 2021. No closed cases were associated with transfusion transmission.

7. Blood stem cells

Blood stem cells can multiply to renew themselves; the new cells develop into blood cells such as red cells, white cells and platelets. In adults, they are found mainly in the marrow of large bones, with a few cells in the bloodstream. The cord blood of newborn babies, taken from the umbilical cord and placenta after the delivery of a healthy baby, is also very rich in stem cells. Blood stem cells can therefore be obtained from the bone marrow, from circulating blood (called peripheral blood stem cells) or from the umbilical cord (cord blood) after a baby is born. Blood stem cells are very important in treating various diseases such as leukemia, lymphoma and multiple myeloma. Canadian Blood Services has a coordinated national stem cell program which includes adult registrants and banked cord blood units. Infectious disease testing for all stem cell products includes the same markers tested for whole blood donations.

Canadian Blood Services’ stem cell registry

Canadian Blood Services Stem Cell Registry is a registry of Canadians who have volunteered to donate either bone marrow or peripheral blood stem cells should a recipient need it at some time in the future. Potential registrants complete a questionnaire which includes risk factors for transmissible infections and are tested for their Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) profile. In 2021 there were about 442,000 registrants in the registry. In total, 452 registrants were identified as potential matches for recipients and had additional testing. This number is lower than previous years. This reduction was primarily caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and fewer registrants being selected for international patients due to travel restrictions affecting the transportation of stem cell donations. One registrant tested positive for HCV.

Canadian Blood Services’ cord blood bank

Canadian Blood Services’ Cord Blood Bank collected cord blood at four sites in Canada in 2021 (Ottawa, Brampton, Edmonton, and Vancouver). Participating mothers at these hospitals who volunteer to donate their baby’s cord blood complete a questionnaire about medical conditions that could be passed on to a recipient, as well as risk factors for transmissible infections. If the donation is suitable for transplantation (i.e., has enough stem cells) with negative results for all infections, the cells are frozen and stored until a recipient needs them. In 2021, there were 424 blood samples from mothers tested and one was positive for HTLV.

8. Donor safety

Donor reactions

Canadian Blood Services takes many precautions to make sure that giving blood is safe for donors. These include a health screening questionnaire and a hemoglobin fingerstick screen, as well as providing refreshments and monitoring the donor after donating. Most donors do not have any problems during or after their donation, but it is important to keep track of any incidents that happen so that donor care can be improved. Definitions of reactions are shown in Table 4.

Table 4: Reaction and definitions

| Reaction | Definition |

|---|---|

| Vasovagal

Moderate Severe |

Donor loses consciousness (faint reactions)

Unconscious less than 60 seconds and no complications Unconscious more than 60 seconds or complications |

| Major Cardiovascular Event | Chest pain or heart attack within 24 hours of blood donation, may or may not be related to donation |

| Re-bleed | The phlebotomy site starts to bleed after donation |

| Nerve Irritation | Needle irritation or injury of a nerve during phlebotomy. Usually described as sharpshooting pain, arm tingling or numbness |

| Inflammation/Infection | Redness or infection at the needle site, usually seen several days after donating |

| Local Allergic Reaction | Rash from skin cleaning solution or dressing, with raised vesicles on the skin |

| Arm Pain | Usually due to blood pressure cuff, tourniquet or arm position |

| Bruise/Hematoma | Temporary dark colour of the skin due to blood leakage from blood vessel at time of phlebotomy |

| Arterial Puncture | Needle inserted in an artery instead of a vein |

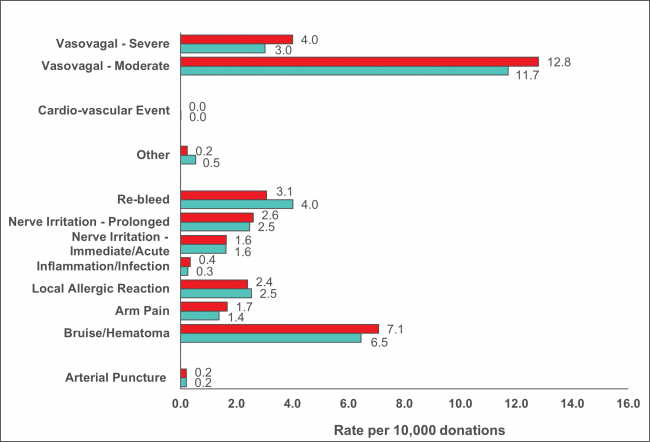

Reaction rates per 10,000 whole blood donations in 2021 are shown in Figure 6 with those in 2020 for comparison. Moderate vasovagal reactions were not significantly different (p= 0.06) while severe reactions were significantly higher (p<0.01). People more likely to experience a reaction are first-time donors, young donors (17-25 years old) and female donors. The reaction reporting system is oriented towards capturing moderate and severe reactions. Most reactions are mild, such as feeling faint or bruising at the needle site, but these are only recorded if mentioned by the donor at some point after donation. A further breakdown of fainting reactions (both moderate and severe) in whole blood donors by sex and donation history is provided in Table 5.

Table 5: 2021 Fainting (vasovagal) reactions (per 10,000 collections)

| Donation Status | Moderate & Severe (all) | Associated with injury | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| First Time | 70.5 | 95.0 | 3.4 | 8.7 |

| Repeat | 6.5 | 17.2 | 0.4 | 1.2 |

|

Injuries were generally not severe such as bruises and cuts from falling *all comparisons (male vs female, first time vs repeat) are statistically significant among moderate & severe reactions combined (p<0.01). For reactions associated with injury all were significant (p<0.01). |

||||

To reduce the risk of COVID-19 infection collection sites provided post-donation refreshments as always but asked donors to have them outside of the clinic. Collection sites stopped providing salty snacks and water before donating, although donors were encouraged to have their own before coming to the clinic. Pre-donation water and salty snacks were put in place in 2019 to reduce vasovagal (faint) reactions. Donor instructions to carry out muscle tension exercises while donating continued to be provided. These can also reduce the risk of a vasovagal reaction. Collectively the pre-donation water and salty snacks and muscle tension exercises were part of the Donor Wellness initiative. Figure 7 shows the reaction rates before putting in place the Donor Wellness activities, while they were in place and after stopping the pre-donation water and salty snacks. There was a downward trend in vasovagal reactions for all groups as a result of donor wellness activities. However, an increase in vasovagal reactions was seen when donor wellness activities were reduced due to COVID-19 pandemic, but only statistically significant for male first time and male repeat donors, in part due to small numbers of reactions with large confidence intervals (p<0.01).

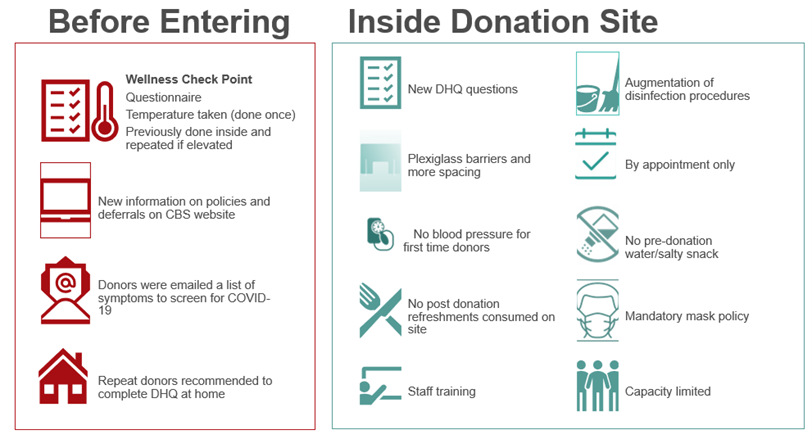

COVID-19 and donor safety

There is currently no evidence that SARS-CoV-2 is blood transmissible. However, there are concerns about (1) infectious risks to donors, volunteers and staff at donation sites and (2) risks to the adequacy of the blood supply. Figure 8 summarizes some of the operational changes that were implemented before and after donors entered collection sites. In March 2020 a -2-week deferral for travel outside Canada was put in place (previously only travel outside Canada, the US and Europe was deferrable, with a 3 week travel deferral ). In addition, donors were deferred for 2 weeks after recovery from COVID-19 and for 2 weeks if they had been in contact with someone who had COVID-19. Later donors who had been hospitalized for COVID-19 were deferred for 3 weeks after recovery.

Donor hemoglobin and iron

The most common reason for a donor deferral at the collection site is a failed hemoglobin fingerstick screen. Low hemoglobin is often related to low iron stores. Iron is needed to make hemoglobin which carries oxygen in red blood cells. Studies at Canadian Blood Services showed that iron stores are often lower in females and are further reduced by frequent donation in both females and males. Males with borderline hemoglobin are also more likely to have lower iron stores. To reduce the chance of developing iron deficiency, the hemoglobin concentration required for males was increased from 125 g/L to 130 and the minimum wait time between whole blood donations for females was increased from 56 days to 84 days in 2017. This longer interdonation period allows females more time to build back their iron stores and return to their baseline hemoglobin levels. To reduce the chance of blood shortages if fewer people donated during the pandemic, the minimum hemoglobin was dropped from July 2020 to October 2020 to 120 g/L for females and 125 g/L for males. As shown in Figure 9 the deferrals decreased from 7% to 3.2% (p<0.01) for females and from 1.5% to 0.8% (p<0.01) for males during that period. However, after October the minimum hemoglobin switched back to the original values and deferrals increased, especially in female donors where they were higher than before the pandemic and remained so.

Information about iron and the safety of blood donation can be found at www.blood.ca as well as in the ‘What you must know to give blood’ pamphlet provided to all donors prior to every donation.

9. Diagnostic services

The Diagnostics Services Laboratories provide patient testing, mainly for pregnant women (Perinatal Laboratories) and patients receiving blood transfusions (Crossmatch/Reference Laboratories). Some Canadian Blood Services Diagnostic Services Laboratories provide all of these services.

| Maternal | 98.22% |

| Paternal | 0.73% |

| Cord | 1.05% |

| 170,969 samples tested |

Perinatal laboratories

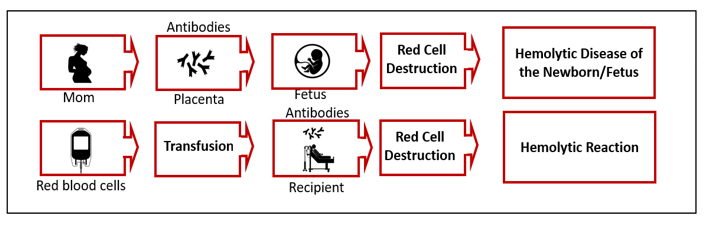

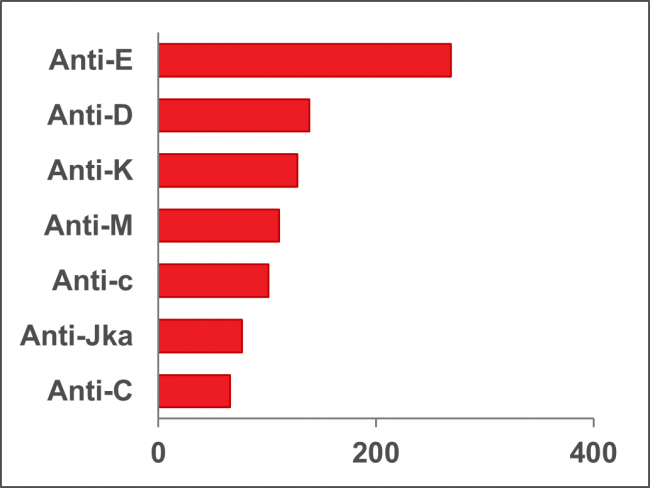

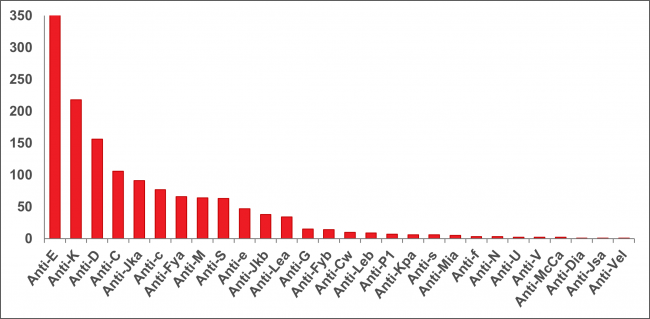

The Perinatal Laboratories provide testing of pregnant patients for blood group and antibodies to red blood cells. Some antibodies can cause hemolytic disease of the fetus/newborn. The goal is to (1) identify Rh negative pregnant patients and recommend treatment to prevent developing anti-D antibodies, and (2) identify pregnant patients with risky antibodies to monitor their pregnancy and treat as needed. Testing of fathers, newborns and fetuses is also sometimes done. In 2021 1,101 pregnant patients had red blood cell antibodies; the most common ones that could put their baby at risk are shown in Figure 10.

Note: Anti M is rarely clinically significant

Crossmatch/reference laboratories

The reference laboratories provide testing of patients for blood groups which must match the donor blood to be transfused. They also carry out antibody investigations for patients who may have unusual red blood cell antibodies and need special matching of blood for transfusion. Figure 11 shows the frequency of different antibodies in pre-transfusion patients (2,165 patients). Patients who have rare antibodies/antigens may be difficult to match for transfusion. The National Platelet Immunohematology Platelet Reference Lab in Winnipeg, Manitoba assists health care providers manage thrombocytopenic patients by HLA and Human Platelet Antigen (HPA) typing and investigation for HLA and HPA. HLA and HPA typed platelets are available for transfusion support of these patients.

For more details see https://blood.ca/en/hospital-services/laboratory-services/surveys

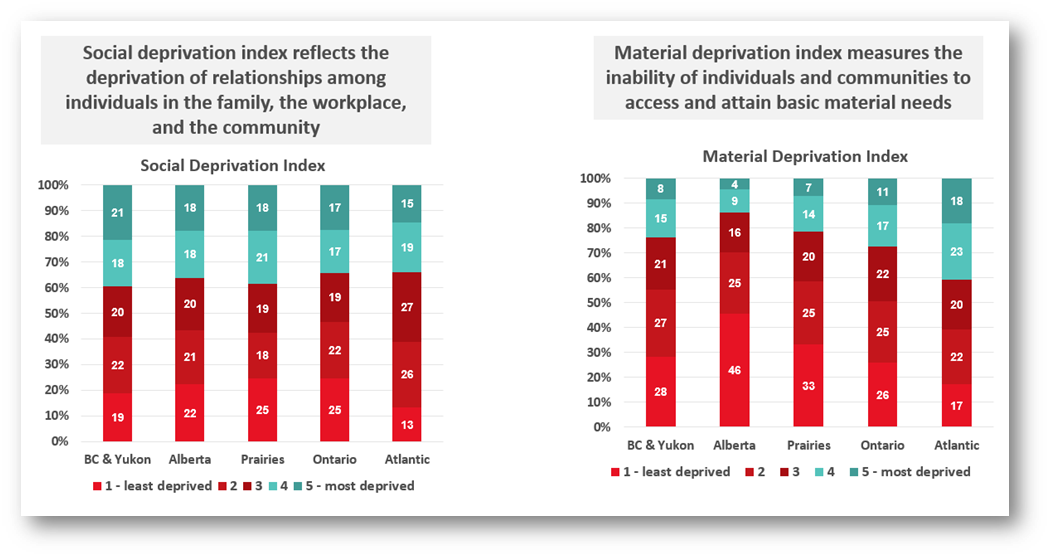

10. Donor demographics

The proportions of whole blood donations by demographic variables are shown in Figure 12 and Figure 13. All blood donors are asked a voluntary question about their racial/ethnic group, which assists the laboratory in selecting donor samples for additional testing for rare blood groups that are more frequent in certain populations. Over 95% of donors answer this question. While most donations are given by donors who self-identify as white (81%), the ethnicity of racialized donors varies by geographic region. Most donations are repeat donations, a little more than half from males, nearly half (45%) from persons over 50 years of age, and nearly half (46%) are from Ontario.

References

Donor Screening

Goldman M, Butler-Foster T, Lapierre D, O’Brien SF, Devor A. Trans people and blood donation. Transfusion 2020;60:1084-1092.

Vesnaver E, Goldman M, O’Brien SF et al. Barriers and enablers to source plasma donation by gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men under revised eligibility criteria: protocol for a multiple stakeholder feasibility study. Health Res Policy Sys 2021;18:131.

O’Brien SF, Goldman M, Robillard P, Osmond L, Myhal G, Roy E. Donor screening question alternatives to men who have sex with men time deferral: Potential impact on donor deferral and discomfort. Transfusion 2021;61:94-101.

Saeed S, Goldman M, Uzicanin S, O’Brien SF.Evaluation of a Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP)/ Post Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP) Deferral Policy among Blood Donors Transfusion 2021;61:1684-1689.

Germain M, Gregoire Y, Custer BS, Goldman M, et al. An international comparison of HIV prevalence and incidence in blood donor and general population: a BEST Collaborative study. Vox Sang 2021;61:2530-2537.

Goldman M. How do I think about blood donor eligibility criteria for medical conditions? Transfusion 2021;61:2530-2537.

Caffrey N, Goldman M, Osmond L, Yi QL, Fan W, O’Brien SF. HIV incidence and compliance with deferral criteria over three progressively shorter time deferrals for men who have sex with men in Canada. Transfusion 2022;62:125-134.

Residual Risk

O’Brien SF, Yi Q-L, Fan W, Scalia V, Goldman M, Fearon MA. Residual risk of HIV, HCV and HVB in Canada. Transfus and Apher Sci 2017; 56:389-391.

O’Brien SF, Gregoire Y, Pillonel J, Steele WR, Custer B, Davison K, Germain M, Lewin A, Seed CR. HIV residual risk in Canada under a three-month deferral for men who have sex with men. Vox Sang 2020;115:133-139.

Babesia microti

O’Brien SF, Delage G, Scalia V, Lindsay R, Bernier F, Dubuc S, Germain M, Pilot G, Yi QL, Fearon MA. Seroprevalence of Babesia microti infection in Canadian blood donors. Transfusion 2016;56:237-243.

Tonnetti L, O’Brien SF, Gregoire Y, Proctor MC, Drews SJ, Delage G. Prevalence of Babesia in Canadian blood donors: June-October 2018. Transfusion 2019;59:3171-3176.

O’Brien SF, Drews SJ, Yi QL, Bloch EM, Ogden NH, Koffi JK, Lindsay LR, Gregoire Y, Delage G. Risk of transfusion-transmitted Babesia microti in Canada. Transfusion 2021;61:2958-2968.

Drews SJ, Van Caeseele P, Bullard J, Lindsay LR, Gaziano T, Zeller MP, Lane D, Ndao M, Allen VG, Boggild AK, O’Brien SF, Marko D, Musuka C, Almiski M, Bigham M. Babesia microti in a Canadian blood donor and lookback in a red blood cell recipient. Vox Sang 2022;117:438-441.

Hepatitis E

Fearon MA, O’Brien SF, Delage G, Scalia V, Bernier F, Bigham M, Weger S, Prabhu S, Andonov A. Hepatitis E in Canadian blood donors. Transfusion 2017;57:1420-1425.

Delage G, Fearon M, Gregoire Y, Hogema BM, Custer B, Scalia V, Hawes G, Bernier F, Nguyen ML, Stramer S. Hepatitis E virus infection in blood donors and risks to patients in the United States and Canada. Trans Med Rev 2019;33:139-145.

Bacteria

Ramirez-Arcos S, Evand S, McIntyre T, Pang C, Yi QL, DiFranco C, Goldman M. Extension of platelet shelf life with an improved bacterial testing algorithm. Transfusion 2020;60:2918-2928.

Malaria

O’Brien SF, Ward S, Gallian P, Fabra C, Pillonel J, Davison K, Seed CR, Delage G, Steele WR, Leiby DA Malaria blood safety policy in five non-endemic countries: a retrospective comparison through the lens of the ABO risk-based decision-making framework. Blood Transfus 2019;17:94-102.

HTLV

O’Brien SF, Yi QL, Goldman M, Gregoire Y, Delage G. Human T-cell lymphotropic virus: A simulation model to estimate residual risk with universal leukoreduction and testing strategies in Canada. Vox Sang 2018;113:750-759

Zika Virus

Germain M, Delage G, O’Brien SF, Grégoire Y, Fearon M, Devine D. Mitigation of the threat posed to transfusion by donors traveling to Zika-affected areas: a Canadian risk-based approach. Transfusion 2017;57:2463-2468.

Murphy MS, Shehata N, Colas JA, Chassé M, Fergusson DA, O’Brien SF, Goldman M, Tinmouth A, Forster AJ, Wilson K. Risk of exposure to blood products during pregnancy: guidance for Zika and other donor deferral policies. Transfusion 2017;57:811-815.

COVID-19

Stanworth SJ, New HV, Apelseth TO, Goldman M et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on supply and use of blood for transfusion. The Lancet Haematology 2020;7:757-764

Saeed S, Drews SJ, Pambrun C, Yi QL, Osmond L, O’Brien SF. SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence among blood donors after the first COVID-19 wave in Canada. Transfusion 2021;61:862-872.

Drews SJ, Hu Q, Samson R, Abe KT, Rathod B, Colwill K, Gingras AC, Yi QL, O’Brien SF. SARS-CoV-2 virus-like particle neutralization capacity in blood donors depends on serological profile and donor-declared SARS-CoV-2 vaccination history. Microbiol Spectr 2022;10:e0226221.

Reedman CN, Drews SJ, Yi QL, Pambrun C, O’Brien SF. Changing patterns of SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence among Canadian blood donors during the vaccine era. Microbiol Spectr 2022 dpi: 10.1128/spectrum.00393-22.

Iron Deficiency

Goldman M, Uzicanin S, Osmond L, Yi QL, Scalia V, O’Brien SF. Two year follow-up of donors in a large national study of ferritin testing. Transfusion 2018;25:2868-2873.

Goldman M, Yi QL, Steed T, O’Brien SF. Changes in minimum hemoglobin and interdonation interval: impact on donor hemoglobin and donation frequency. Transfusion 2019;59:1734-1741.

Chasse M, Tinmouth A, Goldman M et al. Evaluating the clinical effect of female donors of child-bearing age on maternal and neonatal outcomes: A cohort study. Transfusion Medicine Reviews, 2020;24:117-123.

Blake JT, O’Brien SF, Goldman M. The impact of ferritin testing on blood availability in Canada. Vox Sang 2022;117:17-26.

Donor Wellness

Goldman M, Uzicanin S, Marquis-Boyle L, O’Brien SF. Implementation of measures to reduce vasovagal reactions: Donor participation and results. Transfusion 2021;61:1764-1771.

Goldman M, Germain M, Gregoire Y, Vassallo RR, Kamel H, Bravo M, O’Brien SF. Safety of blood donation by individuals over age 70 and their contribution to the blood supply in five developed countries: a BEST Collaborative group study. Transfusion 2019; 59:1267-1272.

Appendix I: Implementation dates of testing

| Marker | Implementation Date* | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Syphilis | 1949 | |

| 2 |

HBV (Hepatitis B Virus) |

||

|

|

HBsAg |

1972 |

|

|

|

Anti-HBc |

2005 |

|

|

|

HBV NAT |

2011 | |

| 3 |

HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus) |

||

| Anti-HIV-1 EIA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) | 1985 | ||

|

Anti-HIV-1/2 EIA |

1992 | ||

| HIV-1 p24 antigen | 1996 (discontinued in 2003, resumed in 2021) | ||

| HIV-1 NAT | 2001 | ||

| Anti-HIV-1/2 (including HIV-1 subtype O) EIA | 2003 | ||

| 4 |

HTLV (Human T-Lymphotropic Virus) |

||

| Anti-HTLV-I | 1990 | ||

| Anti-HTLV-I/II | 1998 | ||

| 5 |

HCV (Hepatitis C Virus) |

||

| Anti-HCV EIA/ELISA | 1990 | ||

| HCV NAT | 1999 | ||

| 6 |

WNV (West Nile Virus) |

||

| WNV NAT | 2003 | ||

| 7 | Chagas’ disease (Trypanosoma cruzi) selective testing | 2010 | |

| 8 | Bacteria | ||

| BacT Alert | 2004 | ||

| BacT Alert modified for 7 day platelets | 2017 | ||

|

*These are the dates that testing for the marker began. Tests have been upgraded as new versions of the test became available. |

|||

Appendix II: Rate of HIV, HCV, HBV, HTLV and syphilis in first-time and repeat donations

(Note that these graphs have different scales on the y-axis)

Appendix III

All HCV NAT reactive re-tested samples were reactive on both platforms (Roche [Canadian Blood Services, CBS] and Abbott [Public Health Agency of Canada National Microbiology Laboratory, NML]). Of NAT non-reactive samples 17 (74%) were reactive on both platforms, and 6 (26%) were non-reactive on the Abbott platform. The 6 discordant INNO-LIA results were reviewed. All had relatively weak signals (e.g. low levels of anti-HCV antibodies) on the Roche system. Three were from repeat donors and considered likely true reactive samples that might have been missed on prior testing. Three were from first time donors; two of these considered likely true reactive and one likely false reactive.